Einsiedeln, the high place of pilgrimage in Switzerland

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

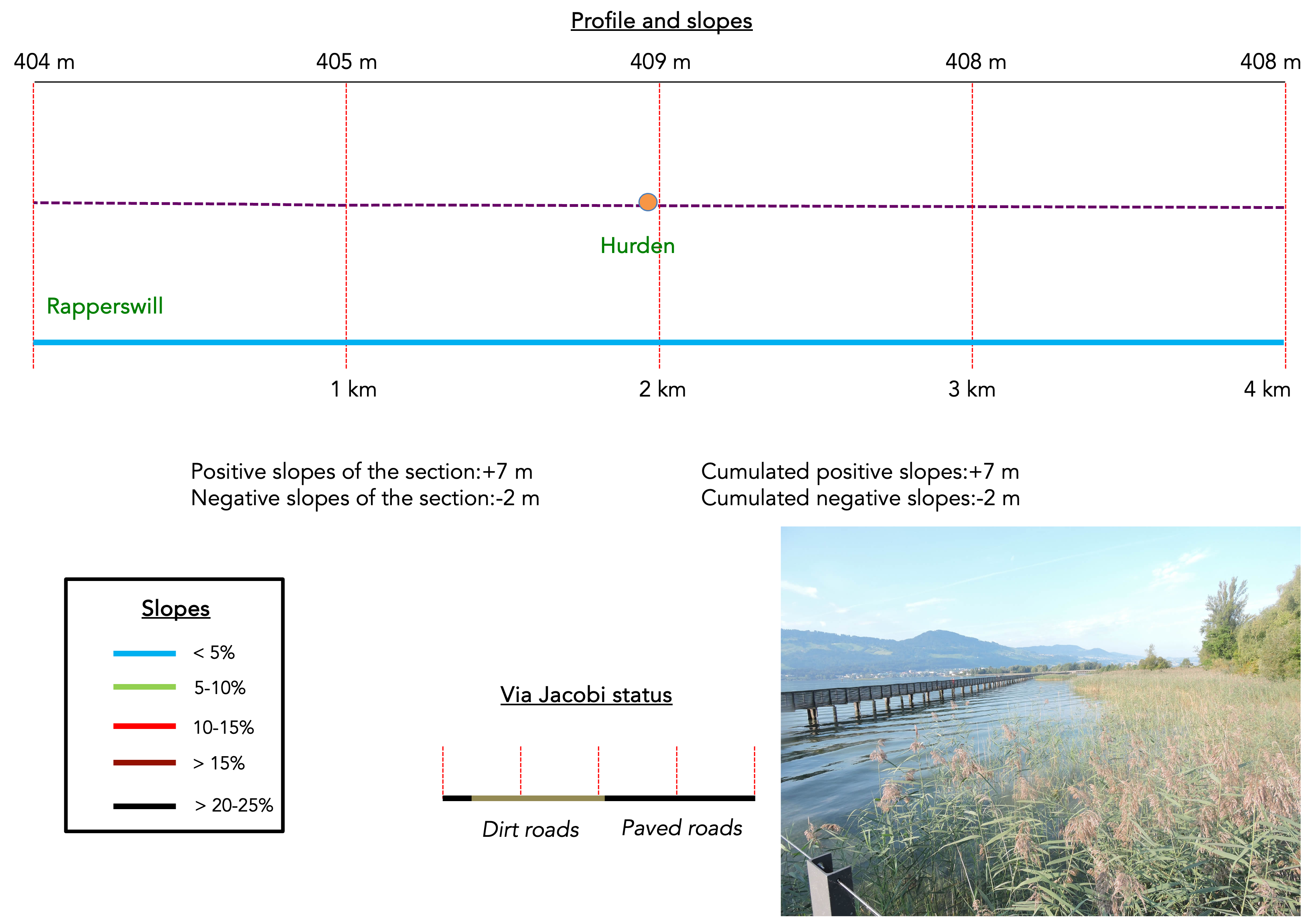

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the route (paved or dirt roads). The courses were drawn on the « Wikilocs » platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-rapperswil-a-einsiedeln-par-la-via-jacobi-4-31971928

|

Not all pilgrims are necessarily comfortable using GPS or navigating routes on a mobile device, and there are still many areas without an internet connection. For this reason, you can find several books on Amazon dedicated to the major Via Jacobi 4 route, which runs through the heart of Switzerland and over the Brünig Pass. The first guide leads pilgrims through the German-speaking part of Switzerland up to Fribourg, while the second continues through French-speaking Switzerland to Geneva. We have also combined these two books into a compact, lighter, and highly practical version. While the descriptions have been slightly condensed, they remain detailed enough to guide you step by step along the way. Recognizing the importance of traveling light, this latest edition has been designed to provide only the essentials: clear and useful information, stage by stage, kilometer by kilometer. The stages have been carefully adjusted to ensure accessibility and alignment with available lodging options. These books go beyond simple practical advice. They guide you kilometer by kilometer, covering all the crucial aspects for seamless planning, ensuring that no unexpected surprises disrupt your journey. But these books are more than just practical guides. They offer a complete immersion into the enchanting atmosphere of the Camino. Prepare to experience the Camino de Santiago as a once-in-a-lifetime journey. Put on a good pair of walking shoes, and the path awaits you. |

|

|

|

|

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

On this day, after having wandered in awe over the majestic wooden viaduct that snakes above the bay of Lake Zurich, you are about to tread the paths steeped in the history of Meinrad, this scholarly monk from the 11th century. His odyssey began on the mountain of Einsiedeln, where your journey passes, before flourishing in the foundation of what would become the venerable Einsiedeln. The monastery of Einsiedeln, a haven of spirituality, opens its doors to a myriad of pilgrims. Annually, more than 500,000 souls converge from the four corners of the globe to pay homage to the Black Madonna. It is also in these places, among the pastures populated with cattle from ancestral Switzerland, that the illustrious Paracelsus was born. A philosopher and alchemist of genius, he was a pioneer of medicine, a prelude to our current knowledge. The panoramas and the bucolic existence unfold here in a splendor that takes your breath away.

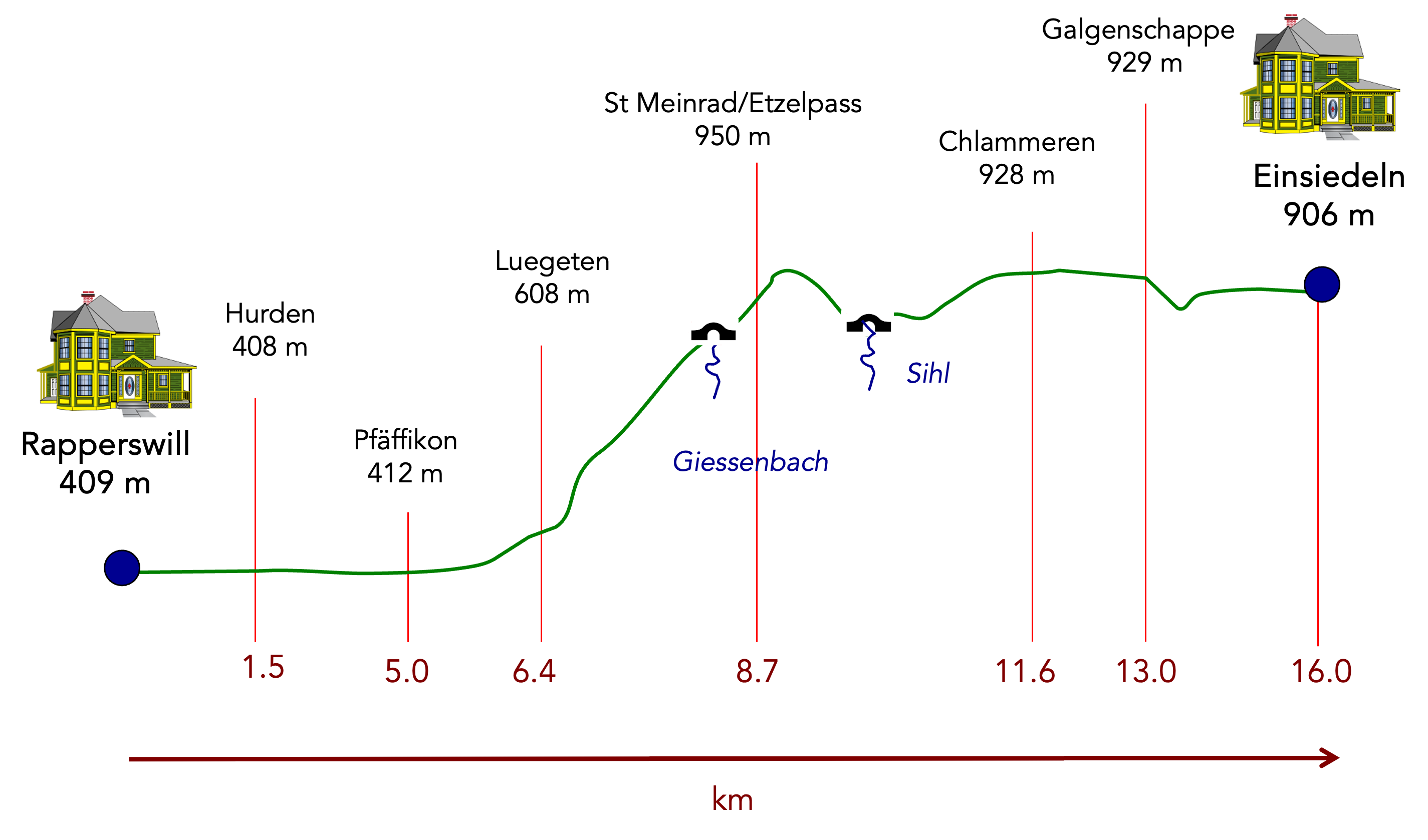

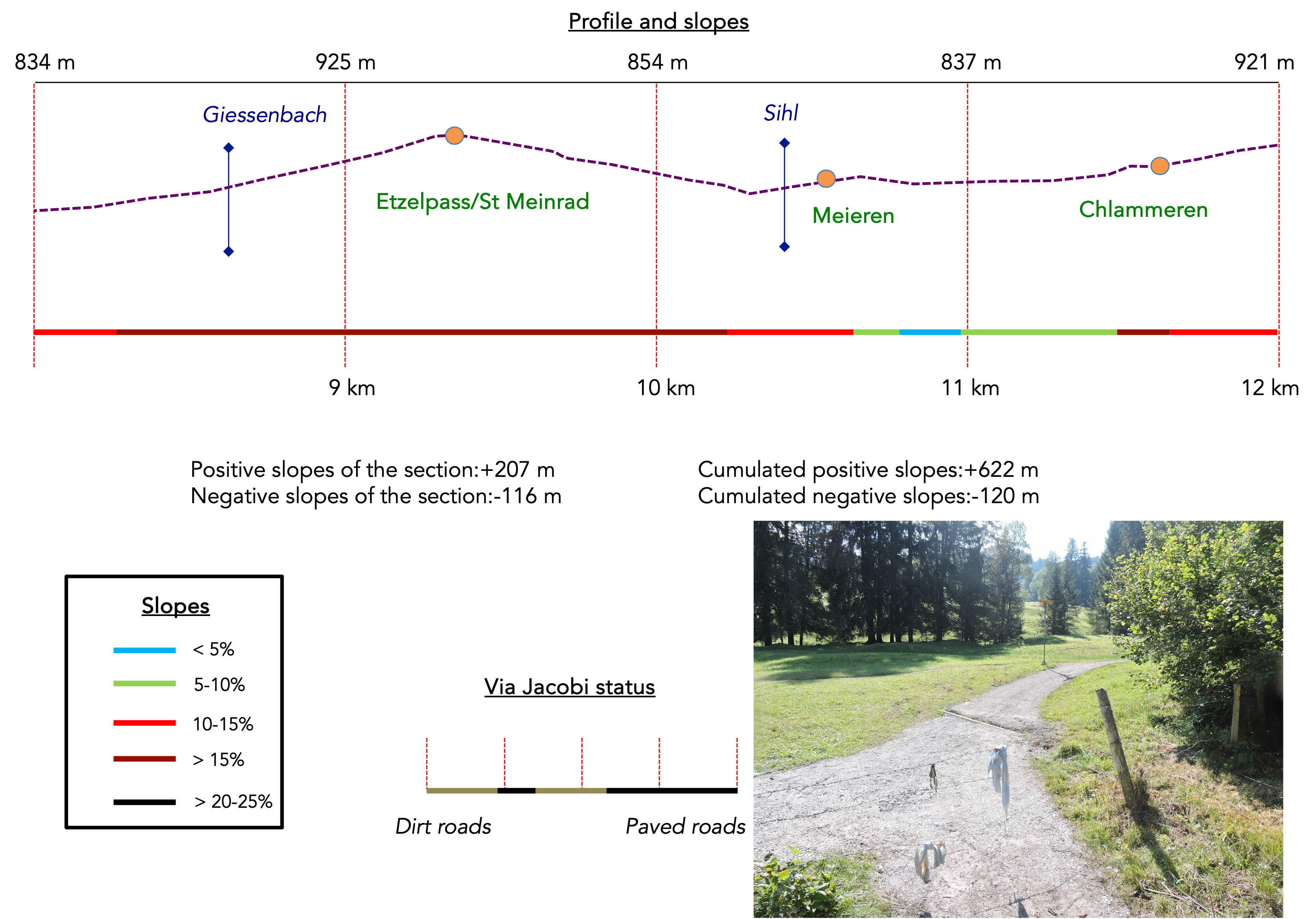

Difficulty level: The terrain of this stage proves to be a considerable challenge, with a significant altitude gain for such a brief crossing (+676 meters/-173 meters). Initially, an esy walk up to Pfäffikon transforms into a test of strength up to the Etzel pass. The ascent towards Luegeten poses as a Herculean trial, with gradients reaching 30%. There, the slopes, though slightly softened, still conceal arduous challenges, with inclinations sometimes skirting 20%. From the Etzel pass, the trail plunges towards the Sihl in a steady descent, before launching, at times mercilessly, towards the heights of Einsiedeln. The descent towards the city is accomplished without trouble.

State of the Via Jacobi: In this stage, the distances on the asphalt exceed those on the paths:

- Paved roads: 9.8 km

- Dirt roads : 6.2 km

Sometimes, for reasons of logistics or housing possibilities, these stages mix routes operated on different days, having passed several times on these routes. From then on, the skies, the rain, or the seasons can vary. But, generally this is not the case, and in fact this does not change the description of the course.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For those seeking « true elevations » and enthusiasts of genuine altimetric challenges, carefully review the information on mileage at the beginning of the guide.

Section 1: A grand and astounding stroll by the lake

Overview of the route’s challenges: of the stroll.

|

The Via Jacobi, gracefully escaping from the embrace of Rapperswil, leaves the shore to launch, with almost poetic boldness, beneath the road and rails, before revealing itself, with sudden tranquility, in front of the ancestral wooden bridge that spans the lake, acting as a link between two worlds. |

|

|

|

| This bridge, a stage for the first morning glows where joggers find their ephemeral paradise, parades with discreet elegance past the Heilig Hüsli chapel, a jewel from 1551, resting, solitary but dignified, on its unique stone pillar. Here, everything is enchanting – the bridge’s framework, seeming to float on the shimmering waters, and the grey planks, like brushes on the canvas of nature. Souls crossing this passage find themselves enveloped in an almost mystical aura, as if standing before the majesty of the Taj Mahal. | |

|

|

| This bridge, a jewel delicately placed on the lake’s bluish fabric, cleaves the horizon, escorted by an army of reeds. The water, of crystal clearness, reveals the aquatic ballets of fish. In 1358, Duke Rudolf IV of Austria, weaver of Rapperswil’s history, ordered the creation of this first wooden passage, uniting Rapperswil to Hurden, driven by designs both spiritual and commercial. Then came, in 1878, the construction of a causeway, a prelude to the advent of the modern bridge and its iron companions. | |

|

|

|

|

| Beyond the bridge, where water and sky blend in an endless embrace, Lake Zurich stretches, vast and undisturbed. | |

|

|

On this human masterpiece, fishermen and dreamers coexist, united in a constantly renewed wonder at the grand spectacle before them.

| The adventure of the Via Jacobi, after marrying the causeway, gently allows itself to be guided towards the reassuring firmness of solid ground. | |

|

|

| The route then meanders through Hurden, this hamlet where the charm of holiday resorts and the tranquility of lakeside homes blend. | |

|

|

| There are truths whispered with nostalgia. After the memorable crossing of the bridge from Hurden, the rest of the route loses its splendor, its joy, turning into a less exhilarating journey towards Pfäffikon station, a short but dense trip, where nature gives way to asphalt and the forced sharing of the path with cyclists, in the heart of traffic. You are now in the canton of Schwyz, and Pfäffikon draws near. | |

|

|

The only beautiful panorama is when the lake merges on both sides of the bridge.

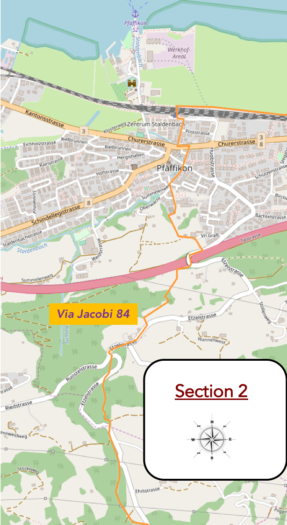

Section 2: A serious bump towards Luegeten

Overview of the route’s challenges: Look at the profile, you will not be disappointed. Right from the exit of Pfäffikon, it’s sometimes more than100 meters of elevation gain per kilometer.

| At one point, you can cross to the other side of the road and follow along the railway track. But, it’s just as feasible to stay on the road until reaching the station. Either way, the station must be reached, in a city that is not the most beautiful in the region. It is primarily a city where companies flock. Here, the taxes for companies are around 10%. Total happiness, right? So never mind, you’ll work here and prefer to live in Rapperswil. | |

|

|

|

|

| Near this station, the Via Jacobi takes off, aspiring towards the city’s heights in search of the Etzelpass.

You will notice here that the direction indicates both the Via Jacobi 4, the main route of the Camino de Santiago in Switzerland, and the Via Jacobi 84. You deserve a little explanation. For pilgrims who followed the Koblenz variant from Lake Constance, it is indeed the Via Jacobi 4. But for you, who followed the Rorschach variant, passing through Schmerikon and then Rapperswil, the route also remains on the Via Jacobi 84. But don’t worry: the two routes merge and remain together until Einsiedeln. |

|

|

|

| The journey weaves, snaking between stairs and narrow alleys, dancing amidst a patchwork of homes, where modern meets old sparingly. | |

|

|

|

|

| Higher up, you leave the urban confines to embrace a trail that crosses the meadows, under the benevolent yet distant gaze of farms, austere witnesses of a less pronounced beauty than in St. Gallen lands. | |

|

|

|

|

| The Via Jacobi, on its journey, later caresses the place known as Im Gräfi, a prelude to an ascent towards the pass, crossing the highway as if to challenge the modern world. | |

|

|

| Then comes a climb, where each step is a struggle, an embrace with the slope of Luegeten, where happiness mingles with nightmare, depending on the prism of your endurance. | |

|

|

|

To catch your breath, the gaze can surrender to the contemplation of the lake, down to Rapperswil, a living tableau where the landscape becomes a balm for the soul. |

|

|

|

|

Here, the slope rebels, proudly displaying its 30% challenge, where steps sometimes stand as allies to walkers. |

|

|

|

|

Throughout the ascent, the whisper of the highway rises, like a melancholic choir, coming to caress and sometimes torment the spirit of the walker. Almost at the crest of this hill, Luegeten reveals itself, reminding that sometimes, looking back allows one to better measure the journey taken, rather than fearing the remaining road. |

|

|

|

|

A few last stairs, and the route to the Luegeten pass is unveiled, offering a long-awaited deliverance. |

|

|

|

|

Luegeten reveals itself, almost exclusively, as a panoramic sanctuary where languages and cultures mix, drawn by the promise of a limitless horizon. |

|

|

|

And on its terrace, the world unfolds before your eyes, a final farewell to Lake Zurich, in a sigh of contentment.

Here in Luegeten, a sign once again reveals the ambiguity of the routes: the Via Jacobi 4 and the Via Jacobi 84. The confusion with the routes of the Via Jacobi 4 is constant because it is not unique. If you start from Rohrschach, you will walk on the Via Jacobi 4 up to Schmerikon, before reaching Einsiedeln via the Etzel Pass. But if you start from Koblenz, you will also walk on another variant of the Via Jacobi 4. And to add even more confusion, there is yet another variant of the Via Jacobi 4 that starts from Luzern and joins the main Via Jacobi 4 shortly before Fribourg. Simple, isn’t it, the administration of SchweizMobil!

|

Here, the road to Etzel gradually fades, giving way to a trail that dares to climb into the forest, in search of mysteries. |

|

|

|

|

Higher up, the trail and the road to the pass cross again, in a ballet of nature and asphalt. |

|

|

|

|

In the embrace of this forest, the world becomes magic, where the roots of beech trees, like tentacles of sea legends, edge the ground with their phantasmagorical presence, offering passersby an escape into another world. These trees with shallow roots, play at octopuses and extend their arms that snake over the ground, like gorgons. A real treat for Sunday cyclists! |

|

|

|

|

Not far, the murmur of the Sumelenbach stream accompanies your progress, announcing the approach of a clearing, an oasis of light in the heart of the shadow. |

|

|

|

|

Higher up, you arrive at the place known as Schnäggenburg where the road to the pass also runs. This is not the road to Einsiedeln. It’s just a narrow mountain road, used by mountain enthusiasts to go to the Etzel pass. |

|

|

|

|

The path then continues its course on the edge of the forest. |

|

|

|

|

Then, it returns to the forest. With their imposing silhouettes, their branches adorned with lichens, the trunks of the beech trees rise very high into the sky, like gothic cathedrals, and intertwine their branches with those of the white fir and spruce, which do not want to be part of the review. The slope, as if soothed, becomes less steep. |

|

|

|

|

You arrive in the Bannwald forest, and soon, a refuge, a haven of serenity, is revealed in a clearing, promising a break most likely deserved. |

|

|

|

|

The Gruebi refuge, built in 2016 at the edge of Bannwald, stands as a testament to the generosity of the souls here, offering wood and saw to warm hearts and bodies. The people here are quite exceptional. |

|

|

|

|

Nearby, a shed, cradle of joyful buzzing, where bees dance in a ceaseless ballet, capturing the very essence of life. It’s pure magic around here. |

|

|

|

Section 3: High above, in the hermitage of the good monk

Overview of the route’s challenges: significant ups and downs- terrain.

|

At the refuge, you are not far from the pass. The slope consents, for a time, to soften its harshness within the forested embrace. In this domain, where altitude holds court in the empire of spruces, nature orchestrates a symphony of streams, born of the Giessenbach. These veins of crystalline water carve their path with elusive grace, their routes defying any attempt at precise mapping. |

|

|

|

|

|

||

Here, signs are plentiful, evoking hidden junctions, promises of encounters with the other possibilities of the route.

|

At the forest’s edge, the path nearly grazes the pass road. Far from the hustle of major thoroughfares, this discreet road leads to Einsiedeln. A trail then traverses a landscape dotted with anti-tank barriers—silent witnesses of a time when the Swiss army, in numbers, rivaled Europe’s greatest forces. What enemy would have dared disturb the peace of these heights? |

|

|

|

|

Soon, like a lighthouse guiding lost souls, St Meinrad reveals itself, perched atop its sacred mountain. |

|

|

|

|

Just one final effort, a steep slope to conquer, and the Via Jacobi takes possession of the Etzel pass, reigning at 928 meters above sea level. From the lake, your steps have triumphed over more than 500 meters of verticality. From here, you will only have one directional sign, that of the Via Jacobi 4, all the way to Geneva. That’s better, isn’t it ? |

|

|

|

|

The chapel of St Meinrad, a 17th-century edifice, and the neighboring inn, shaped by centuries, stand where Meinrad, a monk from Reichenau in the 9th century, chose to live as a hermit before sowing the seeds of what would become Einsiedeln. Two ravens, according to legend, were the hermit’s companions, witnesses to his tragic fate at the hands of brigands. Today, their effigy watches over Einsiedeln, the heraldic emblem of the town. Here, the soul feasts on serenity at the chapel, and the body finds comfort at the inn, whose terrace offers a plunging view of the Einsiedeln valley. |

|

|

|

|

Descending the pass via the road unveils a landscape straight out of a Swiss postcard—ancestral farms, vivid green meadows, peaceful cattle, and distant mountains composing a near-unreal harmony. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Further down, the road makes its way past a Christmas tree farm, adding a poetic note to the scene. |

|

|

|

|

It then descends, winding between meadows and herds until it reaches the Krone hotel, located not far from the bridge over the Sihl. |

|

|

|

|

|

It is here (but not at the Krone hotel), that Paracelsus was born in 1493, born Philippus Theophrastus Aureolus Bombastus von Hohenheim. He spent most of his life in Salzburg, where he died. He was an innovative physician-surgeon in therapeutics, coupled with a great philosopher, initiating the shift from Galenic medicine, centered on the four humors, to modern medicine based on biochemistry, destabilizing the Galenic and Aristotelian edifices and paving the way for experimental physiology. Paracelsus’s thought is the starting point of the long process of separating chemistry from alchemy. The work of many scholars over two and a half centuries allowed us to free ourselves from Paracelsus’s metaphysical excesses and, relying on laboratory experiments, to arrive at the chemical revolution of Lavoisier in the 18th century.

It is quite astonishing to find Paracelsus here, in the midst of the gray cows of so-called primitive Switzerland!

|

The Via Jacobi crosses here the Devil’s Bridge, a magnificent stone bridge with its wooden roof, dating from 1700. It was built to transport stones from the Etzel quarry to Einsiedeln for the construction of the new monastery. Crossing the bridge was an important milestone for the ancient pilgrims of Compostela. The Sihl originates in the mountains of the canton of Schwyz, crosses the lake of the same name near Einsiedeln, and flows into the Limmat in Zurich. To see, it resembles a rather tumultuous river. |

|

|

|

A bit of advertising here for the St Joseph hotel in Einsiedeln, a refuge for pilgrims, offering a welcome stop, promising rest and comfort.

|

Beyond the bridge, the road climbs slightly towards the scattered homes of Meieren. However, your route does not linger on this road preferring to quickly escape through the meadows. |

|

|

|

|

The trail then crosses a modest tributary of the Sihl, before sloping up, with moderate gentleness, through a woodland dominated by ashes and beeches, where small gray cows watch you pass, imbued with a wholly pastoral benevolence. |

|

|

|

|

Then, facing a more demanding slope, the trail joins a wider path, an ascent that will test your endurance before finally leading us towards the heights and farms of Chlammeren. The peasants here, too, have their own drivable path for their tractors. Well! We’ll say we understand, given the incline of the meadows here. |

|

|

|

|

A little further up, a small road leads to the farms of Chlammeren. |

|

|

|

Here, a refreshment bar is not just a simple refuge to quench your thirst; it is also a trove of artisanal treasures, offering travelers a taste of paradise.

Section 4: Descending towards Einsiedeln, the Meinrad monastery

An overview of the route’s difficulties: a route without difficulty.

|

Beyond the hamlet, the climb continues with infinite gentleness, ascending towards a high plateau. Before you, in the majestic mountain range, emerge the two characteristic prominences of the Mythen, like silent guardians watching over the Alpine land. Tomorrow, your route will cross them, guided by the whims of the Via Jacobi. |

|

|

|

Soon, you arrive at the place known as Höchmatt, a high-altitude meadow where the air’s breath is as pure as that of the summits. Here, you are at the same level as the Etzel pass, according to a sign indicating Einsiedeln is about an hour’s walk away.

|

The Via Jacobi, carried away by an imperceptible descent, follows the layout of the old Etzel pass road. On the horizon, the silvery silhouette of Lake Sihl, a majestic body of water fed by the mountain streams, where the eponymous river meanders, while Einsiedeln rests in the valley’s embrace. |

|

|

|

|

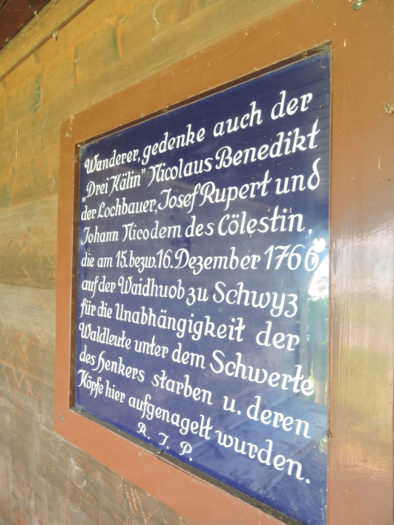

Around the bend, at a place called Galgenchappeli, a memorial commemorates three peasant heroes, unfortunate victims of local uprisings, fallen here under the executioner’s blade in 1766, their heads nailed to the posts of infamy. |

|

|

|

|

The road approaches Lake Sihl, yet does not plunge into it. The lake’s tranquil waters, harmoniously blue, reflect the icy serenity typical of Alpine lakes. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

As you draw closer to Einsiedeln, sacred symbols dot the road, witnesses to a fervor rooted in the centuries. |

|

|

|

|

It is then that the road slightly slops down, as if to show respect towards the city that looms on the horizon. |

|

|

|

|

Even today, anti-tank barriers protect Einsiedeln, reminding of a past here fortunately spared from the torments of history. The city spreads gracefully across a vast plain, under the benevolent gaze of the Mythen, overseeing from the heights. |

|

|

|

|

The Via Jacobi concludes its journey upon reaching Einsiedeln, on the Alte Etzelstrasse, though you remain at a distance from the city’s beating heart. |

|

|

|

|

There, where a breath of the countryside still lingers, Einsiedeln opens its gates to you. |

|

|

|

|

The road now skirts a more recent part of the city, admittedly lacking charm. |

|

|

|

|

Then, it draws closer to the abbey, crossing paths with the St Gangulf Chapel, a secular building dating from the early 11th century. Ancient chronicles, illustrated by the hands of time, trace the passage of the Way of St. James through its sacred walls. The Second World War saw the restoration of this place of worship, testifying to the eternal quest for spirituality. |

|

|

|

|

The Via Jacobi finally emerges in the heart of Einsiedeln, populated by some 11,000 souls, renowned for its monastery but also for its ski jumps which, each winter and summer too, host international ski jumping competitions. |

|

|

|

|

The abbey, dedicated to Our Lady of the Hermits, majestically presides over a vast square, animated by the coming and going of the faithful and the curious. The Einsiedeln convent ranks among the most visited shrines, attracting each year more than 500,000 pilgrims from all corners of the globe to contemplate and venerate the Black Madonna. |

|

|

|

|

|

At the center of this imposing square springs the Virgin’s fountain. Many pilgrims drink from its source, originally the source of St. Meinrad. It is attributed with therapeutic properties.

|

It has already been mentioned that Meinrad, who came from Reichenau, a Benedictine house on an island in the Rhine, first established himself as a hermit, as early as 828, near the Etzel pass. He then descended to Einsiedeln, then in the midst of a dense forest, to live in a few rooms, with a small chapel for worship. In 861, he was killed by thieves who crushed his skull. The hermitage of St. Meinrad was then abandoned for 40 years. Other monks took over the hermitage. They restored the chapel and cleared the surrounding area. In 934, the small monastic community, following the Rule of St. Benedict, expanded, and a first Abbot was appointed. In 947, Emperor Otto recognized the monastery and conferred upon the abbots the dignity of princes of the Empire. Einsiedeln shone with bright brilliance in the 10th and 11th centuries, and its influence spread over southern Germany. From the 14th century, its pilgrimage attracted large crowds. It should be noted that it was in 1286 that mention was first made of a chapel dedicated to the Virgin. On the altar where Meinrad prayed, a chapel was built, the site where now stands the Chapel of Grace, where pilgrims from all over the world have come and continue to come to venerate the Black Madonna. A difficult period followed with numerous fires, frictions between the cantonal authorities and the monastery, the Reformation. In 1577, a last fire destroyed the village and a large part of the monastery. Reconstruction was undertaken. In 1683, the Chapel of Grace, containing the precious statue and the old hermit’s chapel, was transformed, completely covered in black marble at the expense of the Archbishop of Salzburg. The almost total reconstruction of the monastery was decided in 1702. The current façade, with its tall towers, was completed in 1724. The grand square in front of the church was arranged from 1745 to 1747. Living in the full Baroque era, the buildings were designed as such. In the 18th century, given the increasing number of pilgrims, some transformations were made in the naves, around the Chapel of Grace, and in the arrangement of the great organs. Let’s enter the church. |

|

|

|

|

Lovers of late Baroque and rococo will find their delight. The object of devotion is in the Chapel of Grace, the Black Virgin, the Madonna of the Hermits. The statue, made of pear wood, measures about 1 meter. Of unknown origin, it is said to have been brought here in the middle of the 15th century. Originally, the face and hands were painted, but the soot from the candles burned eventually blackened them. It was then decided to paint the main parts of the statue black. Despite successive fires, the statue and its chapel remained intact. The Virgin was secured during the occupation of French troops in the Revolution of 1798. Before each major religious festival, the statue changes costume, and the monks change her dress several times a year, in red, purple, white, blue, or Persian robes. There are no less than 33 ceremonial outfits, made of precious fabrics, adorned with jewels, gold crowns, necklaces, pearl rosaries, or diamond earrings. There is a responsible for the Marian wardrobe in the convent. Covering a Black Virgin is not unique to Einsiedeln. It is practiced similarly, for example, at Le Puy-en-Velay or Rocamadour. In Catholic liturgy, the beginning of a jubilee year is always solemnly marked by the opening of the Holy Door by the pope at St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican. However, for this Jubilee of Mercy, Pope Francis wished that in each diocese there be a holy door so that everyone around the world can make a jubilee journey. Einsiedeln undertook the step by erecting a door in front of the church. |

|

|

|

| The massive abbey contains 4 courtyards. In addition to apartments for the monks, it includes a school, workshops, a cellar for the abbey’s wine, stables housing horses raised by the monks, a library not open to the public. The monastic library holds manuscripts and books dating back to the monastery’s foundation in the 10th century. There are now about fifty monks. The canton of Schwyz is a predominantly Catholic canton. | |

|

|

|

|

|

The city’s life is concentrated near the church and the adjacent streets. Beautiful buildings adorn the square, including the baroque Rathhaus or the St Joseph hotel, an institution here. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Even the banks here are entitled to their flourishes. |

|

|

|

|

That Sunday, there was a crowd in Einsiedeln. It wasn’t just the ski jumpers training for the competition. It was an alpine festival, rarely seen anymore except in German-speaking Switzerland, in the large towns. « The Swiss man milks his cow and lives happily, » said Victor Hugo. Nothing has changed along the entire route of the Way of St. James, up to Lausanne. Cows, more cows, nothing but cows. In Einsiedeln, there was a crowd to watch the procession of whip crackers, but especially the bell ringers. Only the Alphorn players and the wrestlers in breeches were missing to complete the tour of Swiss folk heritage. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

And after this rather dissonant symphony, the break, of course, takes place at the canteen, to the sounds of a traditional orchestra. Obviously, it’s better to skip the canteen and enter one of the restaurants, where you will eat the best Rösti on the planet. |

|

|

|

Accommodation on Via Jacobi

- Hôtel-restaurant Rössli, Hudnerstrasse 137, Hurden; 055 416 21 21; Hotel, dinner, breakfast

- Familie Dillier, Lützerhof, Etzelstrasse 126, Pfäffikon; 055 420 21 93/079 604 14 50; Guestroom (straw), dinner, breakfast

- Ferienwohnung Kählin, Pilgerweg 36, Pfäffikon; 055 410 56 20/079 240 35 72; Guestroom, breakfast

- Seedamm Plaza, Seedammstrasse 3, Pfäffikon; 055 417 17 17; Hotel****, dinner, breakfast

- Gasthaus St Meinrad, St Meinrad; 055 412 25 34; Hôtel, dinner, breakfast

- Kloster Einsiedeln, Einsiedeln; 055 418 61 57; Accueil chrétien, dinner, breakfast

- Jugend und Bildungszentrum, Lincolnweg 23, Einsiedeln; 055 418 88 88; Youth hostel

- B&B Wissmüli, Weissmühlestrasse 3, Einsiedeln; 055 412 51 58; Guestroom, breakfast

- Zen Ermita, Etzelstrasse 38, Einsiedeln; 078 408 10 89/076 405 05 67; Hotel (zen), dinner, breakfast

- Hôtel Sankt Joseph, Am Klosterplatz, Einsiedeln; 055 412 21 51; Hotel, breakfast

- Hôtel Allegro, Lincolnweg 23, Einsiedeln; 055 418 88 88; Hotel**, dinner, breakfast

- Hôtel Sonne, Hauptstrasse 82, Einsiedeln; 055 412 28 21; Hotel**, dinner, breakfast

- Hôtel Sankt Georg, Hauptstasse 72, Einsiedeln; 055 418 24 24; Hotel***, breakfast

- Hôtel Drei Könige, Paracelsuspark 1, Einsiedeln; 055 418 00 00; Hotel***, dinner, breakfast

- Hôtel Linde, Schmidedenstrasse 28, Einsiedeln; 055 418 48 48; Hotel***, dinner, breakfast

Finding accommodation on this stage shouldn’t pose major difficulties. You’ll be in cities with all the necessary amenities. However, it’s still wise to make reservations for peace of mind.

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

Next stage : Stage 4b: From Schmerikon to Einsiedeln |

|

Back to menu |