In the monotony of the Broye Valley

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

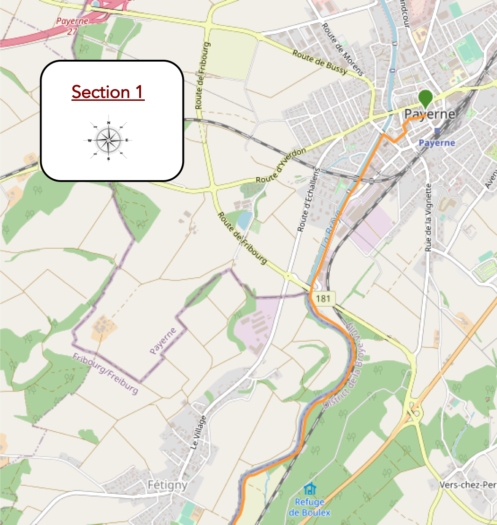

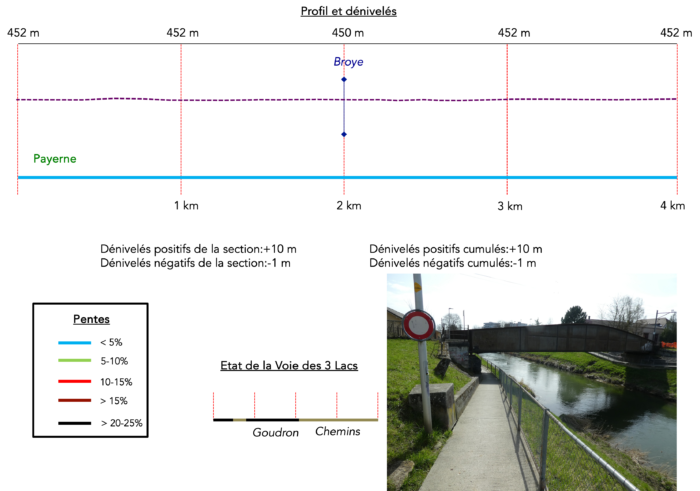

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the route (paved or dirt roads). The courses were drawn on the « Wikilocs » platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-payerne-a-moudon-100111723

| It’s clear that not all travelers are comfortable using GPS and navigating via smartphone, and there are still many areas without an internet connection. As a result, you find a book on Amazon that covers this journey.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page. |

|

The Broye is often viewed as a straight, tamed, and monotonous river, bordered by long rows of poplars. Many pilgrims might find this section lacks charm or excitement—a real « way of the cross, » so to speak. The river underwent extensive corrections and canalization in the 19th century, and even earlier, to manage frequent floods and contain its overflow. The restoration of the river also helped reclaim significant land for agriculture, making the Broye Valley one of Switzerland’s most fertile plains. While this route may not appeal to lovers of wild and varied landscapes, it is still appreciated by cyclists and dog walkers. Let’s not be overly negative, though. After passing through such beautiful landscapes since Basel, a little monotony can’t hurt. Along the way, you’ll also witness the remarkable efforts made by a diverse group—comprising fishermen, farmers, and ecologists—to restore the river to its former natural state. Canalization had stripped the river of much of its life. Many animal and plant species could no longer thrive there, with fish being unable to pass over the high thresholds of tributaries, and the river sometimes reaching excessive temperatures. Local farmers had grown accustomed to pumping the river’s precious water to irrigate their fields. Fortunately, these issues have been addressed, and many signs along the path describe this impressive initiative.

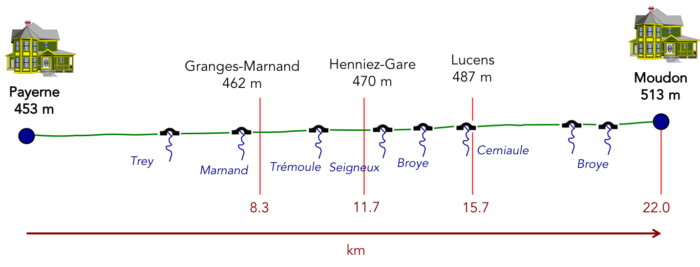

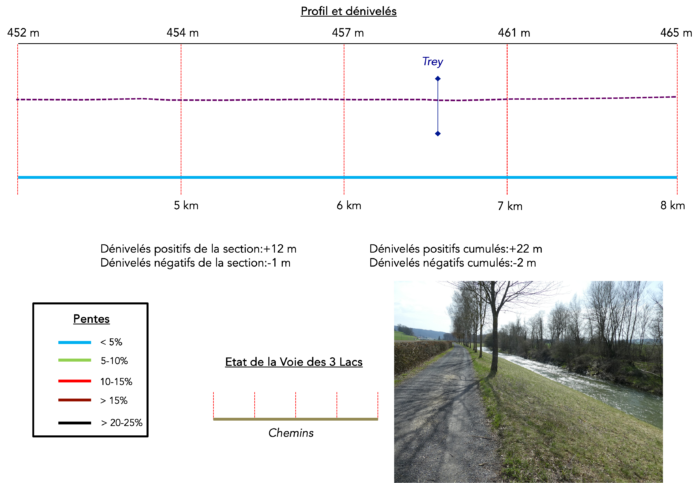

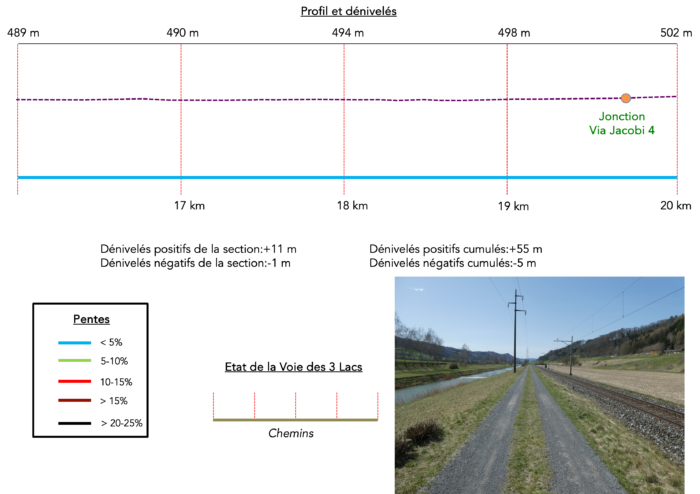

Difficulty level : The elevation changes today are minimal: +70 meters/-6 meters, following the gentle rise of the river.

State of the Three Lakes Trial : Today’s walk mostly takes place on a wide dirt road:

- Paved roads: 2.9 km

- Dirt roads : 19.3 km

Sometimes, for reasons of logistics or housing possibilities, these stages mix routes operated on different days, having passed several times on these routes. From then on, the skies, the rain, or the seasons can vary. But, generally this is not the case, and in fact this does not change the description of the course.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For those seeking « true elevations » and enthusiasts of genuine altimetric challenges, carefully review the information on mileage at the beginning of the guide.

Section 1 : Leaving Payerne

Overview of the route’s challenges : The route presents no challenges.

|

The Three Lakes trial, a trail whose name remains as a promise of lakeside landscapes, retains its title even after leaving the lakes near Avenches. This route resumes in the center of Payerne, heading west towards the Broye River. From the majestic cathedral, the marked trail, with its distinctive yellow sign characteristic of Swiss paths, winds through the town and its methodically laid-out streets. |

|

|

|

|

|

| The route quickly leads to the river, which appears as an aquatic horizon. |

|

|

|

| As you proceed, you will pass an old, rustic tower, a silent witness to the past, followed by the Catholic Church of Our Lady of the Immaculate. It is important to note that Payerne is located in the canton of Vaud, a region deeply influenced by Protestantism. | |

|

|

| At the church, the road reaches the river. However, it does not cross it. The Broye River, fluid and capricious, flows from west to east, linking Moudon to Payerne. You will follow the river upstream almost continuously, beginning on its right bank. | |

|

|

| A short stroll along the river, interspersed with charming little bridges, leads you out of the town. You then enter the suburbs, where tall buildings, often lacking charm, sometimes enlivened by colorful graffiti, stand by the water’s edge. | |

|

|

|

|

| But as is often the case in most suburban areas, this pleasant walk quickly turns into an industrial zone, where the constant noise of rental activities adds to the cacophony of the environment. Fortunately, the river, despite the less romantic surroundings, gently ripples along its calm course. | |

|

|

|

|

| The route leaves Payerne for good as it meets the Fribourg Road, a peripheral route that bypasses the town. Major roadways, such as the Lausanne-Bern Road and the nearby highway, carefully avoid Payerne. At this point, signs indicate that you are walking along the Via Jacobi 4, an incorrect statement since Via Jacobi 4 only begins after Moudon. Nevertheless, you are on the right track, with Moudon about five hours’ walk away. | |

|

|

| If you pass through here on the weekend, you’ll find a small square filled with picnickers. Payerne, a vibrant town with a large, diverse community of foreign workers, offers a lively and cosmopolitan scene. | |

|

|

| From this point onward, the route will accompany you along the river for an extended period, all the way to Moudon. Initially, asphalt follows the railway, providing a clear path. From Payerne to Moudon, the route follows a simple trio: the river, the road or trail, and the railway. A minimalist but predictable itinerary. | |

|

|

| Shortly after, the asphalt gives way to gravel, marking a gradual return to nature. | |

|

|

| The trees lining the path are mostly clusters of beeches, tall and straight, often sprouting new shoots, along with a few rarer deciduous trees such as oaks, birches, and poplars. | |

|

|

| A little further on, the path draws closer to the railway, which it will soon leave behind, but it will always remain nearby. The trail avoids the woods and instead follows the contours of hedgerows, offering a simple, unvaried landscape. | |

|

|

| The road often continues in a nearly straight line. Across the river to the right is the village of Fétigny, located in the canton of Fribourg. The geography here is particularly complex, with the canton of Vaud extending almost to Murten in the canton of Fribourg, creating a kind of enclave. The local residents are likely the only ones who know exactly to which canton they owe their taxes. | |

|

|

Section 2 : Walk along the river

Overview of the route’s challenges : The route presents no challenges.

| On these paths, where time sometimes seems to stand still, one must learn to notice the details—those little things that, suddenly, pull you from the torpor. For instance, your gaze might linger on the sight of riders on horseback on the other side of the lake, riding along the hedgerows—fleeting silhouettes that bring a touch of life to this almost motionless landscape. | |

|

|

| Or perhaps it’s the train, a modest regional convoy, slicing through the plain, never far from the path you are following. Its regular passage reminds you of the steady pace of time in this tranquil valley. | |

|

|

| A bit further, the dirt road makes a slight bend, a rare shift in this mostly linear route. This subtle turn leads you towards the vast horticultural farms. | |

|

|

| You then run by large sheds where horticulturists bustle around their enormous greenhouses. Here, flowers and plants seem to overflow from every direction, a riot of organized chaos, bursting with color—a striking contrast to the austerity of the road. | |

|

|

| On weekends, the scene changes entirely. Cyclists and Sunday riders flood the area, infusing energy into this sleepy countryside, as if each one is trying to capture a piece of the peace that nature so generously offers here. | |

|

|

|

To your left, the vast Broye plain stretches out—one of the few plains in Switzerland, and likely the most cultivated in the country. It is here that the RN1 passes through, the major route connecting Lausanne to Bern. Yet, the motorists who use this road remain discreet, preferring the nearby highway on the other side of the valley. |

|

|

|

|

PFurther on, the road changes character. From gravel, it turns into a dirt path, punctuated down the center by a wide strip of grass, like a verdant ribbon dividing the route. The tall, majestic poplars now replace the birches, their long silhouettes tracing the river’s edge, enhancing the impression of an immobile landscape, frozen in almost solemn tranquility. |

|

|

|

A bridge appears on the horizon, elegant in its simplicity—a quiet marvel of civil engineering. Yet, it is not intended for you. It remains there, unused in your journey, reserving its passage for others. These bridges, despite their splendor, seem to serve little purpose, like treasures that no one comes to claim. People often whisper that Switzerland can afford such extravagances, and there is little doubt of that when you see these nearly unused structures.

|

A bit further, the Trey stream flows into the Broye River. The mouth has been carefully redesigned to allow trout, minnows, and even salamanders to migrate freely from the river. This confluence is a small haven of biodiversity, where aquatic life can peacefully renew itself. |

|

|

|

|

Then, you find yourself again on a long, straight path—endless, monotonous, where the landscape seems to stretch into infinity. Only on weekends does a bit of life return, with the arrival of cyclists. It’s a bit like Holland here, with cycling tourists riding along the river, evoking the canals of that faraway land. |

|

|

|

|

You might think the walk is completely flat, but that’s just an illusion. Look at the river—it never flows in total peace. Gentle ripples sometimes stir its course, reminding you that you are gradually ascending towards its source, even if imperceptibly. Behind the poplars, slightly bent by the valley winds, the village of Granges-Marnand comes into view, appearing from afar as a modest settlement, with its scattered villas and small, timid industrial districts. |

|

|

|

|

|

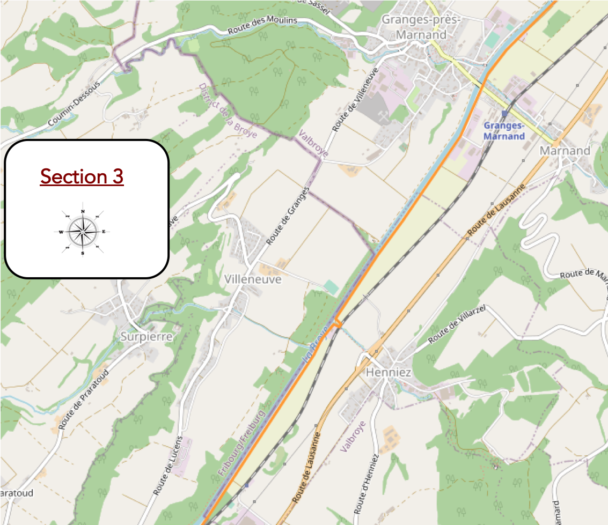

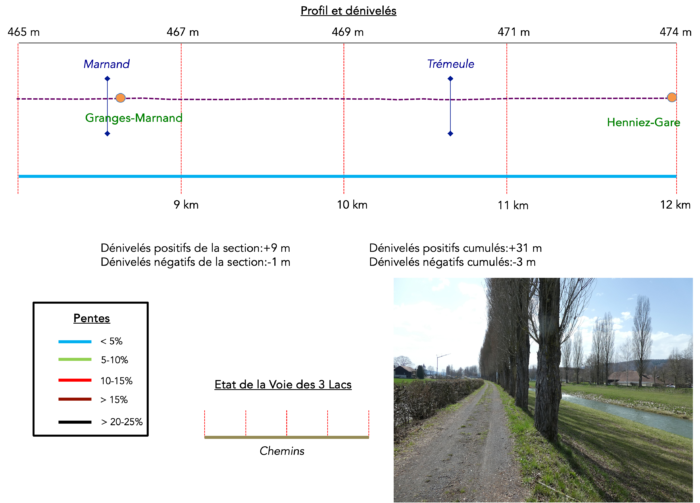

Section 3 : Henniez, the sparkling waters of French-speaking Switzerland

Overview of the route’s challenges : The route presents no challenges.

|

As you approach the village, the road gently winds, leading to the bridge where the small Marnand stream joins the Broye river. A quiet meeting between two bodies of water, which, while merging, continue their journey together towards different horizons. |

|

|

|

|

Granges-Marnand itself straddles the Broye, split between its two banks. The geography here is always surprising, with its enclaves and invisible borders, at the crossroads of the cantons of Vaud and Fribourg. In 2010, several Vaud municipalities merged to create the commune of Valbroye, with Granges-Marnand as its nerve center, although nothing in this tranquil landscape suggests such administrative importance. |

|

|

|

The route barely brushes against this peaceful village. It does not linger, nor does it delve into it, preferring to continue along the river, always on the same bank. The horizon remains unchanged—flat and with no promise of surprises. Here, a sign announces Moudon is more than three hours away on foot, a distance that seems endless in the monotony of this journey. Each step feels like an exercise in patience, and the landscape ahead offers little comfort, promising only the continuation of this never-ending walk.

|

The dirt road continues, slipping discreetly behind the last industrial buildings of Granges-Marnand. The structures gradually fade into the landscape, giving way to the countryside. |

|

|

|

|

This marks the beginning of a new phase of the walk—one of absolute monotony. You now embark on a long, straight stretch of nearly two kilometers. To the right, the river flows lazily along rows of poplars and birches, while to the left, a hedge of bushes hides the view of the plain. To break the routine, you alternate between walking on the soft grass and the rougher, gravelly ground. It’s a scene almost identical to the Via Podiensis in France, with the plain of the Adour. Nothing disturbs this tableau except, perhaps, the distant whistle of the train crossing the valley, reminding you that modernity is never too far away. |

|

|

|

|

|

Then, an obstacle seems to rise before you. The path ends abruptly, as if at a dead end. But fear not: it’s simply to make way for the Trémeule stream, which descends from the wooded hills of Henniez, just opposite. No barriers hinder the passage of trout here, much to the delight of weekend anglers, whom you’ll see in great numbers, rods in hand, along the banks.

|

The path skirts the obstacle discreetly, as if nothing had happened, and continues its tranquil course. It briefly flirts with the railway line before resuming its straight character. To your left stretches the vast countryside of Henniez, where fields seem to roll out endlessly. |

|

|

|

|

|

Switzerland, a land of contrasts and luxury, proves this once again. A little further on, the road runs alongside a beautiful bridge spanning the river, connecting Henniez to Villeneuve on the other side. Yet this bridge is rarely used. Neither horse riders nor vehicles pass over it, and the few pedestrians who do are likely locals, familiar with this short route between Villeneuve and Henniez—two neighboring villages, like two sides of the same story.

|

The waters of Henniez tell the tale of a place at the crossroads of hydrotherapy and the mineral water industry—a story echoed in many other sites of springs or thermal baths. It all begins, as it often does, with rain. Slowly, the water seeps deep into the earth, where it begins a long purification process, passing through geological layers that endow it with purity and minerals. In these depths, the water sometimes remains trapped for years before reemerging, enriched with salts and trace elements. What differentiates one spring from another is the temperature of the water when it resurfaces. In Henniez, the first known spring, called « Bonne Fontaine, » yields water with a temperature ranging from 9 to 11.5°C, depending on the season, drawn from the seven catchments of the famous « Henniez Fault ». |

|

|

|

|

Legend has it that the Celts, and later the Romans, were the first to discover this precious spring. The name Henniez, however, is said to derive from a certain Ennius, a Roman notable who owned land in the region. The 17th century saw the rise of thermal baths all over Europe, and Henniez was no exception to the trend. The Hôtel des Bains was then built near the springs, in the forest overlooking the village. The site thrived, particularly during World War I, attracting wealthy foreigners: pashas from the Orient with their harems, archdukes seeking rest and treatment. But like so many other spa destinations, its success gradually faded with time, and the decades slowly swept away its glory. Efforts were made to revitalize the area by hosting conferences, banquets, or board meetings. But 1939 and the Second World War marked the end of this era. The Hôtel des Bains was converted into a makeshift military post. Today, nothing remains of it, except perhaps in the memories of the old-timers. However, the mineral water industry never ceased. The first bottling plant was inaugurated in 1905, long before the closure of the baths, at a time when Henniez water was sold only in pharmacies as a medicinal remedy. It was only after the Second World War that mineral water began to be consumed daily, gradually shedding its status as a treatment to become a popular beverage. |

|

|

|

|

The path, however, does not pass through the village of Henniez. It skirts it at a distance, at the level of the RN1. Here, monotony reclaims its place, and the route, still as straight as ever, seems to stretch infinitely through the fields of Henniez. A few benches are scattered along the way, but their usefulness is questionable for a reasonable walker, who traverses perfectly flat terrain. |

|

|

|

Skirting the railway line, the dirt road passes close to the Henniez station, though without providing direct access to it. One might wonder why a station exists here, in the middle of nature, far from the village. But by raising your eyes to the hill, you find the answer: just above the station stands the modern Henniez water factory. Perhaps the station exists for official visits or board meetings ?

In 2007, Henniez joined the Nestlé Waters group, following the path of other major mineral water brands, such as Perrier, San Pellegrino, Vittel, and Contrex. Henniez is now the leader in the mineral water market in Switzerland, holding nearly 20% of the market share—a success that even extends to the German-speaking part of the country.

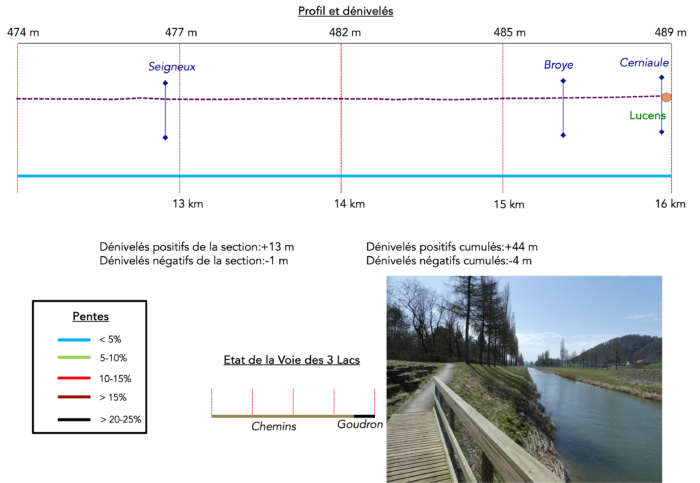

Section 4 : Long walk along the Broye River

Overview of the route’s challenges : The route presents no challenges.

|

The dirt road continues, weaving gently through a slightly denser landscape of woods and bushes. It crosses an almost imperceptible border between the cantons of Vaud and Fribourg, a boundary so subtle only keen observers would notice. Since the abolition of cantonal customs in 1848, few pay attention to these invisible lines—save for a few diligent tax inspectors, perhaps? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The path then approaches a more residential zone but remains on the outskirts, hugging the edges of a sparse woodland. It stays faithful to the river, which has been its steady companion. Here, the Seigneux stream merges quietly into the Broye River, its meeting marked by barely a whisper of sound. |

|

|

|

|

A small wooden bridge, modest and rustic, crosses the stream. Nearby, a simple fish ladder has been constructed—rough-hewn stones arranged to help trout navigate upstream. Step by step, or rather fin by fin, they climb each level, pausing in the pools formed by the current. The peacefulness of this aquatic refuge is occasionally disturbed by early morning or evening anglers, drawn to this spot to catch freshly reintroduced trout. |

|

|

|

|

After crossing the Seigneux, the route temporarily veers off the broad dirt road, taking a quieter, grassy path. . |

|

|

|

|

|

|

This section is perhaps the wildest of the entire route, with a narrow forest trail meandering lazily along the riverbank, as if sharing a whispered secret with the attentive walker. Across the river, spruce trees emerge, adding an unexpected element to the already unusual landscape. The presence of these trees hints at the untamed character of this hidden corner of nature. Occasionally, a lone bench will appear, not intended for the weary hiker but more often occupied by fishermen. These quiet figures sit patiently, their lines stretched into the water, participating in a calm and meditative form of sport fishing that barely stirs the serene atmosphere. |

|

|

|

|

Exiting the sparse woodland, the path crosses a small tunnel under the railway line that runs along the river. |

|

|

|

|

From here, you embark on another portion of the journey, which, while repetitive, offers alternating surfaces of gravel and grass. The straight path leads towards Lucens, with the flat terrain broken only by the river’s gentle undulations, reminding you that the incline, though subtle, is real. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

As you approach Lucens, the trail enters the town’s industrial outskirts. The once soft earth gives way to asphalt, and piles of metal scrap and industrial debris create a less scenic atmosphere. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Shortly after, the path crosses the river near one of the four production sites of Cremo, a flagship of Switzerland’s dairy industry founded in 1927. Cremo’s headquarters are in Villars-sur-Glâne, in the canton of Fribourg. |

|

|

|

|

Here, for the first time since leaving Payerne, you find yourself on the left bank of the river. The silhouette of Lucens Castle begins to appear, although its picturesque presence is somewhat overshadowed by the surrounding industrial area. The small town is also home to Isover, a subsidiary of Saint-Gobain, a global leader in insulation products, including fiberglass for construction and industry. Since 1937, Saint-Gobain has established numerous subsidiaries in Switzerland, providing glass, plaster, and even bathroom and kitchen equipment. |

|

|

|

|

After leaving Lucens’ industrial zone, the path continues to follow the river. |

|

|

|

|

Upon reaching a bridge, you arrive at the entrance to Lucens, though the trail does not lead into the village itself. At this juncture, you have a choice: you can take the road to the left, which will bring you to Curtilles, where you’ll rejoin the main Way of St. James route (the Via Jacobi 4) coming from Fribourg. Alternatively, you can stay on the left bank of the river, joining the Via Jacobi 4 further ahead. This second option is shorter and avoids walking on asphalt. |

|

|

|

Section 5 : Approaching Moudon

Overview of the route’s challenges : The route presents no challenges.

|

The route continues with a minor peculiarity: you’ll cross the Cériaule stream in an almost acrobatic manner, eventually passing beneath the bridge leading to Curtilles. |

|

|

|

|

However, you remain on the left bank of the Broye River. The dirt road, with a grassy strip in the center, skirts the sports fields of Lucens and heads towards the RN1 highway. At this point, the typically calm river becomes slightly more turbulent. |

|

|

|

|

As you advance, the path passes under the grand arches of the RN1, the main road linking Lausanne and Bern. |

|

|

|

Once beneath the arches, if you look back, you will see Lucens Castle once again, perched majestically on its rocky outcrop. You may have bypassed Lucens without visiting the castle, which might be for the best since it is not open to visitors. Built in the late 12th century, the castle has been destroyed and rebuilt several times. Originally a defensive fortress and later a noble residence, it has been in private hands since 1801. In 1965, the son of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the famed creator of Sherlock Holmes, acquired the castle and established a museum dedicated to his father’s works. This museum only lasted a few years before being relocated elsewhere in the place.

|

Continuing along the trail, the dirt path curves slightly, flanked by a row of birch trees. The river, having carved its way into the soft sandstone, adds a peaceful ambiance to the walk. |

|

|

|

Here, it’s common to encounter fishermen, rods in hand, enjoying the idyllic setting while angling for trout.

But beneath this calm exterior lies a history far from peaceful. This area, not far from the RN1, was the site of an ambitious yet ill-fated nuclear project. In the pursuit of energy self-sufficiency, Switzerland chose the heavy water method, hoping to find unrefined uranium deposits in the Alps. However, on January 21, 1969, a significant incident occurred: the Lucens reactor experienced a partial meltdown. This experimental reactor, which carried hopes for Swiss nuclear independence, met a tragic end.

That morning, operations started as usual with the reactor slowly increasing in power. At 6:15 am, a minor anomaly was detected in the cooling system, yet the decision was made to continue raising the reactor’s power. By 5:20 pm, the situation escalated: a sudden drop in pressure in the primary circuit indicated that carbon dioxide was escaping, accompanied by a spike in radiation levels inside the cavern. An emergency shutdown was initiated, sealing the cavern and ending the Swiss reactor project. Although the Lucens reactor was only a fraction of the size of modern reactors, it never restarted. The subsequent decommissioning made the Lucens accident one of the top ten civilian nuclear incidents worldwide. Authorities consistently claimed the risk of contamination for the surrounding population was minimal, with radiation levels not exceeding natural background levels. However, as elsewhere, doubts lingered, particularly with the increase in intestinal cancer cases in the region over the following decades. Experts later concluded that the rise in cancer cases in the Broye region between 1970 and 1990 was “unlikely” to be linked to the nuclear accident. Of course, similar reassurances were made near Chernobyl!

|

The trail resumes its straight course, flanked by the river on one side and the railway on the other, while the RN1 looms above. This long stretch feels endless, with little distraction beyond the rumble of trucks on the highway, the regular passage of trains, and the occasional cyclists and fishermen testing their luck along the Broye’s banks. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yet this monotonous landscape is about to shift. The trail is poised to cross the river, marking a significant turn. Here, the Three Lakes trail officially merges with the Way of St. James (Via Jacobi 4). This junction, however, is subtle and unmarked, as according to trail managers, the recommended bifurcation should have occurred earlier at Lucens, heading towards Curtilles. If you continue straight, you’ll reach Moudon, but through the industrial zone. It’s better to take the bridge here and rejoin the true Via Jacobi 4. |

|

|

|

|

On the other side of the bridge, the landscape remains just as linear. The dirt road continues, straight and seemingly endless, as it draws closer to the industrial outskirts of Moudon, visible across the river. |

|

|

|

|

|

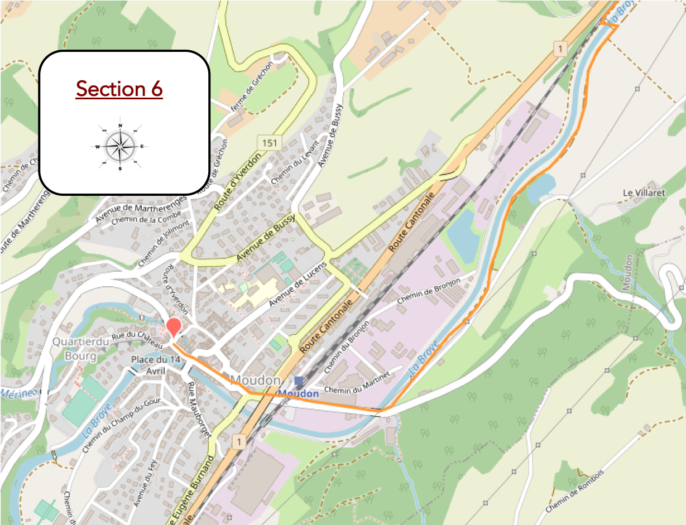

Section 6 : Moudon, capital of the Broye

Overview of the route’s challenges : The route presents no challenges.

|

As you continue, the path heads to a small, tranquil pond—an ideal spot for a quiet break or a picnic. The simplicity of the setting, complete with a visitor shelter, offers a peaceful respite on your hike. |

|

|

|

|

A few hundred more meters along the birch and poplar trees, first on dirt, then on grass, following the river’s edge, and you’ll have a view of the industrial zone across the river. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

At the entrance to Moudon, the route crosses the Broye one last time, not far from a picturesque cheese dairy partially carved into the rock. This crossing adds a local charm to the journey. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

From here, a road leads you towards the train station. |

|

|

|

|

Large parking areas cater to local drivers, though finding a parking spot can sometimes be a challenge—an all-too-common urban dilemma. |

|

|

|

|

Moudon, with its Celtic roots and prosperous Roman era, is now a town of about 6,000 residents. The trail takes you towards the town center, following the Broye and offering a view of the Saint-Etienne Church, often referred to as the “cathedral of the Broye.” This old Catholic church, destroyed by Protestants and restored over the centuries, houses the oldest playable organ in the Canton of Vaud. |

|

|

|

|

Though the town center’s architecture is modest, the upper part of Moudon has more charm. A steep street leads you up to the castle. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

At the top of the hill, where a significant fortress once stood, only the majestic tower and a few ramparts remain. The two « false castles » now standing have been remodeled over the centuries, replacing the original fortress. You’ll find the Château de Carrouge and the Château de Rochefort here, with the latter housing a regional fine arts museum. |

|

|

|

Accommodation on the Three Lakes trail /Via Jacobi

- Regina et Jean-Jacques Duc, Rue de Verdairu 25, Granges-Marnand; 026 668 13 30/079 344 59 93; Accueil jacquaire, dinner, breakfast

- Villa le Cigalou, Route de Moudon 73, Lucens; 026 906 82 35/078 880 22 35; Guestroom, breakfast

- La Ferme du Château, Rte d’Oulens 8, Lucens; 079 759 19 44; Hotel**, breakfast

- Hôtel de la Gare, Avenue de la Gare 13, Lucens; 079 219 33 46; Hotel**, dinner, breakfast

- Dortoir de la Caserne, Moudon; 079 175 97 38; Dormitory

- Piscine du Grand Pré, Moudon; 021 905 23 11; Camping, dinner, breakfast

- Anne et Michel Thorens, Les Combremonts 24, Moudon; 021 905 54 20/078 886 83 07; Guestroom, dinner, breakfast

- Anne et André Mayor, Le Plan 2, Moudon; 021 905 24 06/078 832 30 59; Guestroom, dinner, breakfast

- Michèle Cheseaux, Ch. de Valcrêt 5, Moudon; 079 418 86 47; Guestroom, breakfast

- Hôtel de la Gare, Moudon; 021 905 45 88; Hotel*, dinner, breakfast

- Hôtel du Chemin de fer, Moudon; 021 905 70 91; Hotel*, dinner, breakfast

- French 75, Route du Relais 5, Moudon; 021 905 13 13; Hotel**, dinner, breakfast

The Three-Lakes region is primarily a destination favored by local tourists rather than an international audience. This partly explains why accommodation options are relatively limited, except in towns with a stronger tourism focus, like Murten, which remains the main priority in terms of tourist infrastructure. However, on this particular stage, it is possible to find accommodation and restaurants along the route, even if options may be limited in the smaller localities you pass through. Upon reaching Moudon, the possibilities expand significantly. This more developed town offers a wide range of shops and services, making it an ideal place to rest and stock up after a long day of walking.

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

Next stage : Stage 13a: From Moudon to Lake Sauvabelin/Lausanne |

|

Back to menu |