In the heart of primitive Switzerland

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the route (paved or dirt roads). The courses were drawn on the « Wikilocs » platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-brunnen-a-stans-par-la-via-jacobi-4-32047228

|

Not all pilgrims are necessarily comfortable using GPS or navigating routes on a mobile device, and there are still many areas without an internet connection. For this reason, you can find several books on Amazon dedicated to the major Via Jacobi 4 route, which runs through the heart of Switzerland and over the Brünig Pass. The first guide leads pilgrims through the German-speaking part of Switzerland up to Fribourg, while the second continues through French-speaking Switzerland to Geneva. We have also combined these two books into a compact, lighter, and highly practical version. While the descriptions have been slightly condensed, they remain detailed enough to guide you step by step along the way. Recognizing the importance of traveling light, this latest edition has been designed to provide only the essentials: clear and useful information, stage by stage, kilometer by kilometer. The stages have been carefully adjusted to ensure accessibility and alignment with available lodging options. These books go beyond simple practical advice. They guide you kilometer by kilometer, covering all the crucial aspects for seamless planning, ensuring that no unexpected surprises disrupt your journey. But these books are more than just practical guides. They offer a complete immersion into the enchanting atmosphere of the Camino. Prepare to experience the Camino de Santiago as a once-in-a-lifetime journey. Put on a good pair of walking shoes, and the path awaits you.

|

|

|

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

On August 1st, 1291, a pact of immeasurable significance was sealed, marking the cornerstone of what would become the Swiss Confederation. In the misty valleys of Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden, souls weary from the oppressive yoke of the Habsburg bailiffs bound themselves in a solemn promise, swearing to put an end to the relentless abuses they suffered. This oath intertwines with the immortal legend of the Oath of the Three Swiss. Arnold of Melchtal, son of Unterwalden, driven by a quest for justice for his father’s confiscated cattle, joined on the verdant meadow of Rütli, where the sky brushes the surface of Lake Lucerne, with Walter Stauffacher of Schwyz, and Walter Fürst of Uri, allied by blood to the legendary William Tell. This pact, consolidated and embellished by successive agreements in Brunnen (1315), Sempach (1393), and Stans (1481), wove an unbreakable alliance against the assaults of the House of Habsburg. It unfolded like a majestic oak, embracing other communities, until it erected the Switzerland of 8, 13, and finally 19 cantons. Switzerland today has 24 cantons, with the youngest being Jura, joining the confederation in 1979. Engraved in Latin letters, the original of this pact remains an eloquent testament to those bygone times. In 1891, to celebrate the seventh centenary of this founding act, the Swiss nation united for the first time in celebration, laying the foundations for Swiss National Day, now celebrated every August 1st. In the years following this pivotal pact of 1291, the Waldstätten, choosing their side alongside Louis of Bavaria against the Habsburg claims, faced the fury of Leopold I, Duke of Austria. On November 15, 1315, in the cold embrace of the Morgarten pass, they set an ambush of unparalleled audacity, where the enemy cavalry was annihilated under an unrelenting rain of rocks and tree trunks (1,500 souls felled). Shortly after, the three Cantons, in a renewed spirit of brotherhood, sealed their alliance again in Brunnen. The text of this pact, a faithful echo of the first, strengthened their sacred union. Towards the end of the century, the victory of Sempach over Leopold III forcefully cemented the Eternal Alliance.

Between the shadows of reality and the lights of myth, the history of this pact dances on a tightrope. Scholars, for ages, had pierced the veil of its ordinary essence. Discovered by chance in 1724, after an initial mention around 1530, this document did not shine with uniqueness, as at that time, the art of making pacts was a common refrain in many lands. Its essence was more about securing the commercial routes of the Gotthard than a cry for freedom or resistance. And the tales of William Tell, though woven into the hearts of the Swiss, were but threads of mist, just as the oath of Grütli, whose very existence remains shrouded in mystery. Nonetheless, the original of this pact, if it ever existed, may have been consumed by flames, as was customary in those wooden hamlets. The national celebration, and its anchoring to August 1st, dates only from 1891, not 1291. However, the indomitable spirit of these mountaineers, united against adversity, remains a beacon of victory.

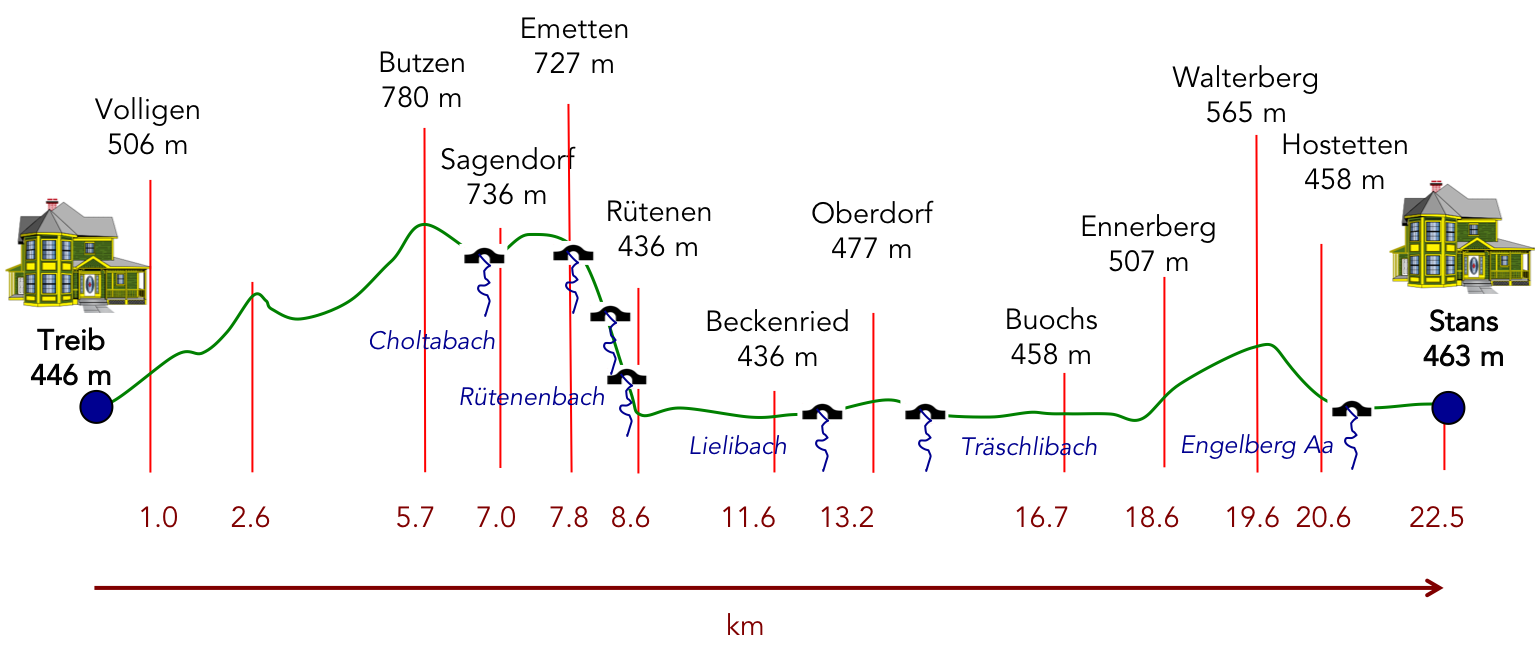

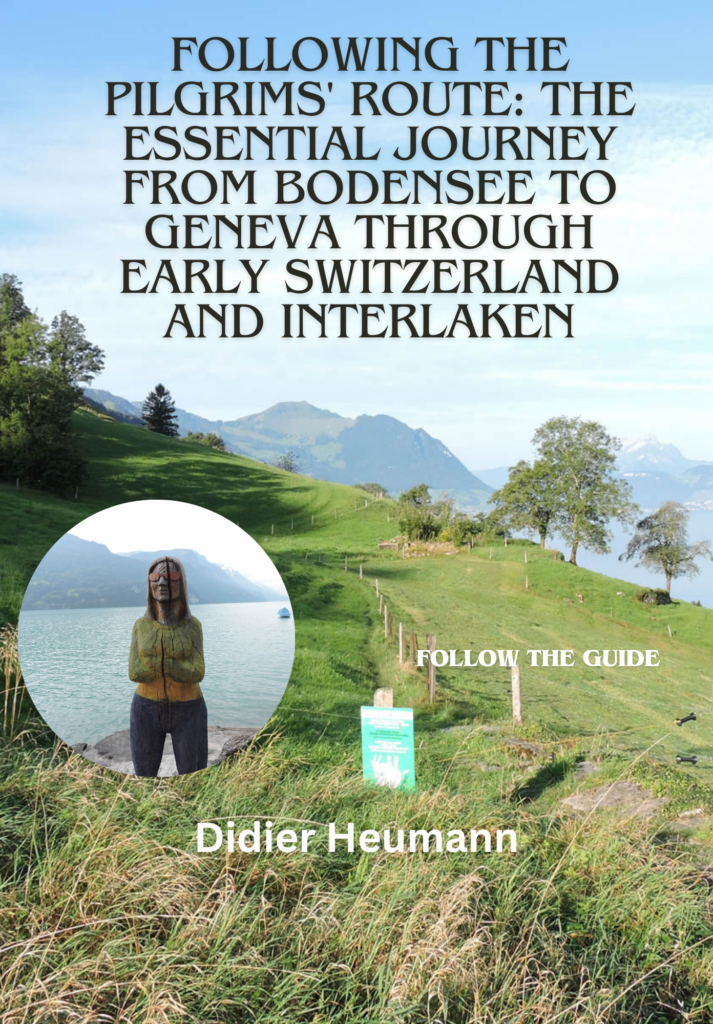

Difficulty level: The journey ahead winds through ancestral forests, sleepy villages, tranquil hamlets, and along the shores of the lake, facing elevations that defy the sky (+763 meters/-714 meters). The ascent is as demanding as the descent, a true test of strength. After a soothing crossing by boat at Treib, the ascent towards the summit of Seelisberg Mountain presents itself as a titanic challenge, with slopes defying gravity, sometimes flirting with 30% gradients under the protective shadow of the cliff. Then comes the vertiginous descent towards the lake beyond Emetten, a journey where every step is an act of faith. But beyond that, the walk softens, caressing the lake shores and foothills leading to Stans, the beating heart of the half-canton of Nidwalden.

State of the Via Jacobi: In this stage, unfortunately, asphalt predominates over the dirt path, a constant reminder of modernity encroaching on the wild nature:

- Paved roads: 16.5 km

- Dirt roads : 5.7 km

Sometimes, for reasons of logistics or housing possibilities, these stages mix routes operated on different days, having passed several times on these routes. From then on, the skies, the rain, or the seasons can vary. But, generally this is not the case, and in fact this does not change the description of the course.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For those seeking « true elevations » and enthusiasts of genuine altimetric challenges, carefully review the information on mileage at the beginning of the guide.

Section 1: Not far from Rütli, the myth of Helvetia

Overview of the route’s challenges: a demanding journey, with slopes often exceeding 15%, beneath the cliffs of Seelisberg.

|

In the heart of Brunnen, your gaze is drawn towards the vastness of Seelisberg, a proud and protective mountain beneath which the Gothard highway winds like a serpent of stone. The horizon, stretching beyond Lake Luzern, reveals Uri and its jewel, Altdorf, while to the right, you catch a glimpse of one end of the lake where Stans nestles discreetly in the canton of Unterwalden. Here, the canton of Schwyz reveals itself in all its splendor. The proximity of Rütli, a green haven at the foot of Seelisberg, seems to echo the legendary oath of the three cantons in 1291, weaving an unbreakable bond between myth and reality.

|

|

|

|

The only route for the traveler, whether pilgrim or hiker, wishing to traverse this haven of nature is to surrender to the caresses of the waves. Thus, leaving behind the bay of Brunnen, you embark towards other shores.

|

|

|

| Your vessel leads you to the port of Treib, where a train, resembling an ascent to the heavens, invites you to conquer Seelisberg. Rütli, guardian of legends, stands there, halfway up, watching over the lake. |

|

|

Beyond the port, a road climbs defiantly towards Seelisberg to the village of Vollingen, where the slope boldly asserts itself.

|

|

|

| Up there, a modest road branches off towards Schwybogen, closer to the water’s edge. However, the Via Jacobi disregards this detour, preferring the promise of the village’s slope. |

|

|

| There, a trail slopes up into the meadows overlooking the village, where the grass, in a typically Swiss burst of green, carpets the ground in a living velvet. |

|

|

| You walk here in the canton of Uri, proud of its emblematic bull. But soon, you will cross the threshold into Nidwalden, this half-canton nestled in the heart of Unterwalden. |

|

|

| The trail trades packed earth for soft grass, climbing still, beneath the intimidating cliffs of Seelisberg, dominating the lake from its protective height. |

|

|

| It then winds, gaining altitude, towards the scattered homes of Walchig, which whisper tales of peasant life and old wood, nestled against the mountain’s flank. |

|

|

| At this moment, you have already conquered a remarkable height, surveying the lake with your gaze, offering a new and dizzying perspective. |

|

|

| Then, the ascent continues, through meadows bordered by cliffs, punctuated here and there by solitary farms, witnesses to alpine tranquility. |

|

|

| Soon, the climb asserts itself, climbing proudly until it intersects a road leading to Seelisberg, at the Triglis intersection. There, a descent towards the lake promises fishing delights, although the slope is no less demanding. But the Via Jacobi ignores the detour. |

|

|

| The cliffs rise like ramparts of a wild citadel, challenging you. But then the road descends towards the lake. Dam! You think it will be even more to climb back up. |

|

|

| It is then that the Via Jacobi, like a spiritual quest, descends onto the road before slipping towards a forest trail, promising to conquer the cliffs of Seelisberg. |

|

|

| The ascent begins gently, the trail flirting with the cliffs, weaving among the deciduous trees, in an embrace of nature and challenge. |

|

|

Section 2: In the Cliffs of Seelisberg

Overview of the route’s challenges: a demanding journey, with slopes often exceeding 15%, beneath the cliffs of Seelisberg.

|

At the outset, the mountain reveals itself under a falsely friendly guise, offering a trail that winds gently along its flank, flirting with the abyss of a greyish cliff. Draped in a cloak of thorny bushes, this cliff is adorned with beech and maple trees clinging to its spine with an almost heroic tenacity.

|

|

|

However, when the time comes to confront the cliff, the slope proves to be intimidatingly steep, often flirting with 30%. The trails, reminiscent of those in alpine heights, carve their way through modest stairs, safeguarded from the abyss by barriers, as if to reassure the traveler in the face of the vast emptiness.

| Yet, the threat of vertigo fades, revealing a path devoid of peril for the adventurous soul, where the Way of St James would never dare to challenge the impossible. |

|

|

As the rocky aridity begins to weigh on the gaze, comfort can always be found by letting one’s eyes wander towards the lake, concealed behind the dancing veil of trees.

| The slope then intensifies, challenging the daring of the hikers on a whimsical trail that, winding through the woods, often sees stumbling steps, slipping with every meter. Soon, the place called Haselholz, a haven of dense forest, reveals itself, sheltering fragrant hazelnut trees under its shade. From there, a steep descent leads to Rütenen, later intersecting the Via Jacobi. The choice of route belongs to the hiker, but whatever the decision, the descent promises to be dizzying. Yet, your route aspires to nobler heights, for the Way of St. James is enamored with summits, especially when crowned with churches or chapels. |

|

|

From this vantage point, Lake Luzern unfolds in all its majesty, with the Rigi opposite, like a stoic guardian above the forest.

| At the peak of this effort, the slope eases, the trail flourishes among the mosses, in a silent ballet with beeches and spruces. |

|

|

| It then emerges onto a sublime ridge, offering a plateau to catch one’s breath, the air perfumed with moss, promising scents of boletes and chanterelles in the right season. |

|

|

| Lower down, the gaze delights in the opening of Weggis, where the lake stretches towards Luzern. The beauty of the lake, in this suspended moment, echoes the pride and sense of independence of the ancient Confederates of the Rütli. |

|

|

| The path, in its momentum, then descends, quickly reaching the hamlet of Butzen, a nest suspended above the world. |

|

|

| Here, a few privileged ones enjoy a breathtaking panorama of the lake, a spectacle continually renewed by the play of light and seasons. |

|

|

| A small road then slopes down gently into the green valley of Seelisberg, on the other side of the ridge. |

|

|

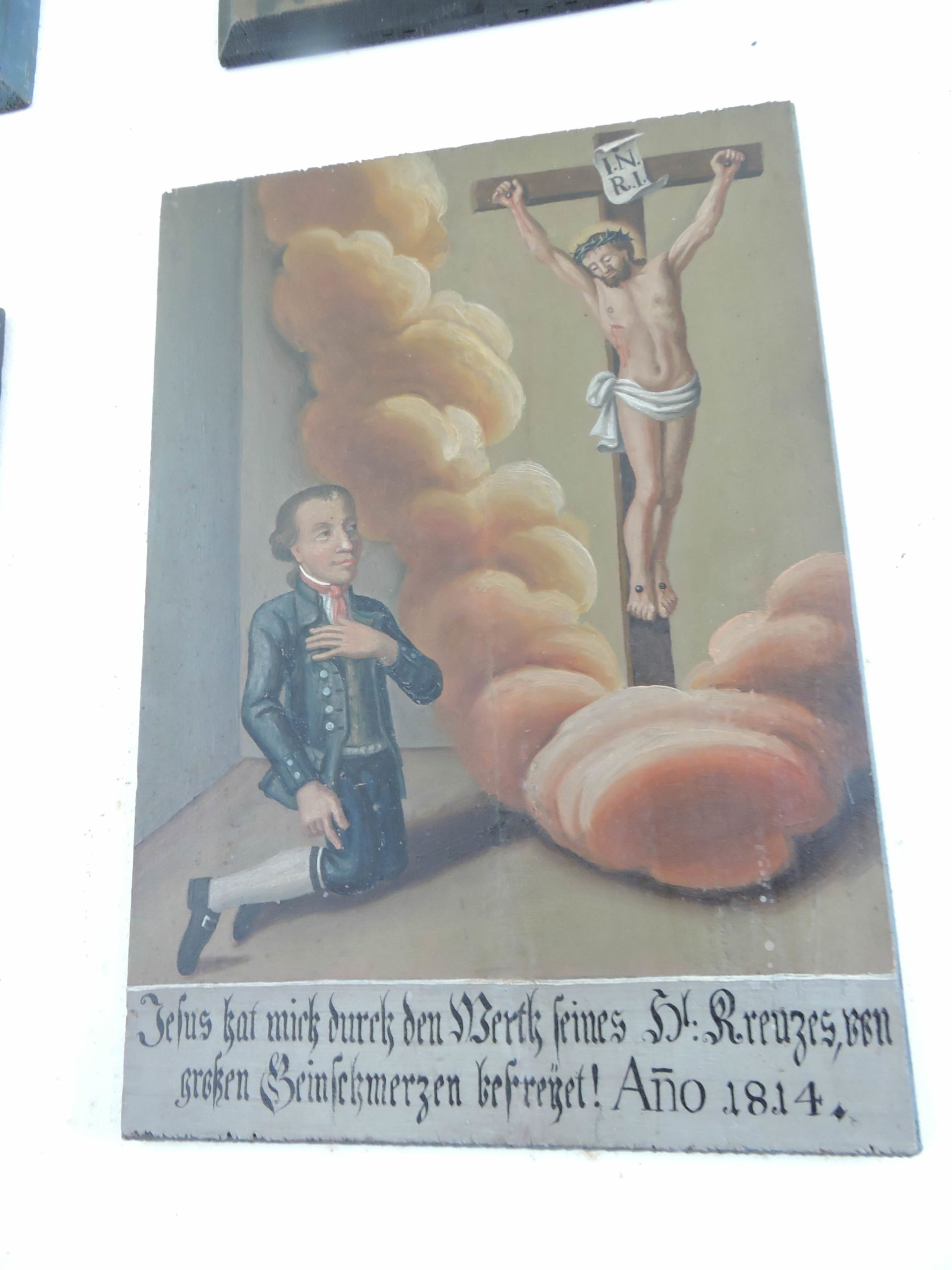

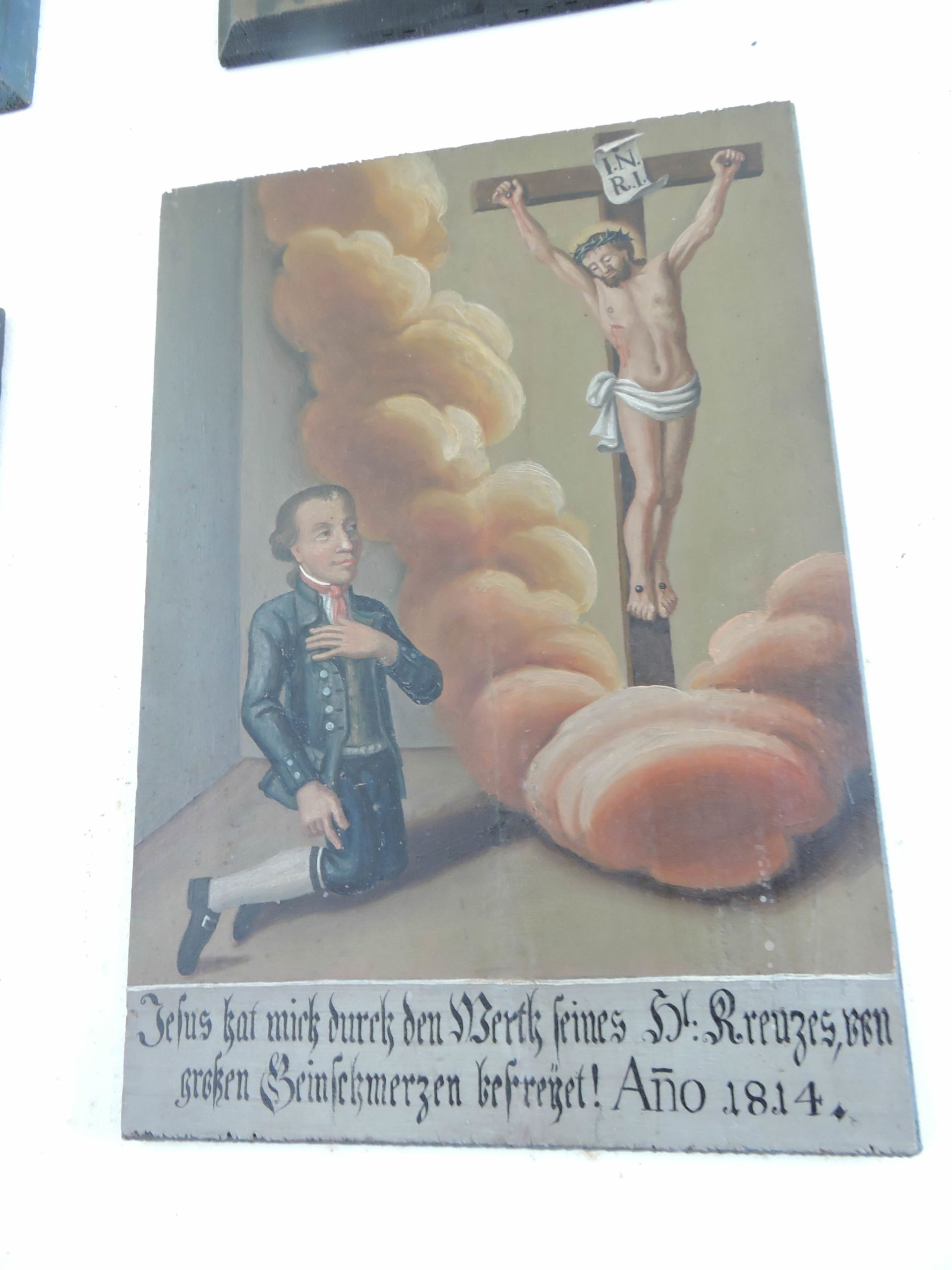

| Along the way, it passes the small chapel of Heiligkreuz. Rebuilt in the 18th century, this chapel holds beautiful naive ex-votos by Franz Joseph Murer, a witness to the local artistic soul. |

|

|

Its striking Dance of Death reminds us of the fragility of our existence.

| Then, the Via Jacobi merges into the Seelisberg road, near the village of Sagendorf, a world still deeply rural. |

|

|

| The village stretches along the Choltabach, a clear water vein in the living fabric of this land. |

|

|

| Further on, the road climbs the valley flank towards Emetten. |

|

|

| The old houses proudly display their shingles or small plaques, witnesses to a Switzerland of ancestral traditions. Here, slopes come alive with various cable cars, and there is passionate indulgence in all forms of flight in a region also known for its skiing and hiking areas. |

|

|

| Crossing a village of some size, this region, once agricultural, sees its face transform. Livestock farming, cheese making, and weaving gradually gave way. In the 1950s, the advent of tourism halted mass emigration. But even today, more than half of its population commutes, its heart beating to the rhythm of the plains. |

|

|

Section 3: Section 3: A real springboard for Lake Luzern

Overview of the route’s challenges: Take flight; you won’t be disappointed.

|

The Via Jacobi winds its way through the bustling heart of the village, weaving between obstacles with the grace of a flowing stream, yet the task is no small feat. It then descends, a journey easily likened to Hercules’ descent into the underworld, towards the shimmering expanse of the lake. Beyond Emetten, perched at an altitude of 770 meters, a trail plunges precipitously 300 meters in just one kilometer, flirting with the boundaries of the impossible, until it reaches the lake, nestled at 450 meters above sea level.

|

|

|

This descent, akin to a test of strength against nature’s whims, is preferably undertaken in dry weather, though pilgrims, valiant but at the mercy of the elements, often cannot choose the conditions. On days when the skies are unforgiving, an alternative route, starting from the Emetten post office towards the hamlets of Häggis and then Ambeissler, provides a less perilous option to rejoin the Via Jacobi in Beckenried.

|

|

|

| The trail, narrow and strewn with obstacles, navigates through a maze of deciduous trees and bushes, its precarious path overlooking the Seelisberg road, which winds like the curves of a slumbering dragon. |

|

|

| Where the stream turns into a cascade, the route becomes an arena where the murmurs of water transform into roars, each step a struggle against the relentless assault of water that leaps, splashes with brute force on a bed of fine stones, all the while being caressed by encroaching mosses. |

|

|

| Halfway down this almost mythological descent, Rütenen and Beckenried appear below like distant oases. The steep slope sometimes gives the impression of a battle against gravity, a tangible vertigo where each step seems suspended above the void. |

|

|

| The trail continues its frenzied descent, a true test of endurance and agility, through a vegetal chaos of wild grasses, maples, and beeches, following the stream in its tumultuous cascades… |

|

|

| … until it meets a reservoir, a prelude to the final confrontation with the highway. In the distance, the Mythen, like eternal guardians, overlook Schwyz and Brunnen, while Gersau, on the other side of the lake, seems to defy the elements. |

|

|

In a final act of defiance, the trail plunges into an extreme descent through meadows, an ultimate test of courage and strength, before crossing the highway emerging from a tunnel, after its journey under the Seelisberg mountain, nearly ten kilometers long.

| It then passes under the highway, where the stream concludes its tumultuous journey, at Rütenen, on the lakeshore, marking the end of this epic. |

|

|

| Here also ends your own odyssey. With the trials behind, it’s time to take a breather, to celebrate the journey! The route levels out, offering a well-deserved respite after such an adventure. . |

|

|

| A peaceful road, still under the shadow of the highway, runs along the lake, a silent witness to your journey. |

|

|

| Numerous streams, anonymous yet fierce in their tranquility, cross this road, as if to remind of the challenges overcome. |

|

|

| The houses, lined up like sentinels along this road, lead to the entrance of Beckenried, some boldly facing the water. |

|

|

| The encounter with the small chapel of Ste Anna, a beacon of the 18th century recently restored, marks the approach to Beckenried. |

|

|

| A small park, like an oasis of calm, offers a breathtaking view of the bay, where Brunnen and the Mythen stand, immutable witnesses to your journey. |

|

|

| The road finally ends in Beckenried, a haven of peace (3,300 souls), welcoming the traveler. |

|

|

| Nidwalden, a bastion of Catholic faith in central Switzerland, houses the St Heinrich church, a Baroque jewel from the late 18th century, watched over by a chapel in the cemetery, symbolizing spiritual perseverance in the face of earthly trials. |

|

|

| Leaving Beckenried, admiration falls on the magnificent traditional houses, testimonies of resilience and elegance in the face of the challenges of time and nature, true emblems of this region in the heart of primitive Switzerland. |

|

|

Section 4: Stroll along Lake Luzern

Overview of the route’s challenges: smooth sailing.

|

Exiting Beckenried, where the blue waters of Lake Luzern shimmer under the benevolent gaze of the mountains, the road crosses the Lielibach, a spirited river gracefully depositing its eroded stones like precious jewels, cascading from majestic heights. Then, akin to a prose poem, in this dance with nature, the road veers away from the shores to reach the neighboring village of Oberdorf, where traditional houses stand proudly, like loyal guardians of ancestral secrets.

|

|

|

| Soon, the road diverges from the silvery banks to immerse itself in the intimacy of Täschlibach, carrying pilgrims’ dreams towards Ridli, where, like a celestial beacon, a chapel stands proudly atop the hill, crowning it like a precious gem in a verdant setting. |

|

|

| Constructed in flamboyant Baroque style, the Ridlikapelle, like a blooming flower in the heart of the valley, unfurls its exquisite embellishments, silent witnesses to the emotions and hopes of past generations. It’s remarkable how many chapels one finds in these regions. |

|

|

| A secondary road gracefully descends from the chapel, gently winding around the pillars of the highway before melding into the tranquility of the lakeshore, inviting travelers to lose themselves in the enchanting symphony of calm waters. |

|

|

| Here, you find yourself back on the main road of the lake. Just a stone’s throw away lies Buochs Beach. |

|

|

| Scarcely after leaving the beach, a discreet road meanders along the azure waters towards Buochs, offering travelers a breathtaking view of the picturesque houses lining the shore, silent witnesses to the history and tranquil life of the inhabitants. |

|

|

| The road gracefully weaves among the stately homes bordering the lake, their colorful facades reflecting the ever-changing hues of the sky, while fragrant gardens perfume the air, inviting travelers to linger and contemplate the simple beauty of life. |

|

|

| Among the inhabitants of these fertile lands, the resilient farmers stand out, offering eager visitors the delights of Sbrinz and Appenzeller cheeses, the golden treasures of fresh eggs, and the generosity of local sausages. And for those who dare, a Kräuter elixir capable of igniting the senses and revealing the mysteries of the surrounding hills. |

|

|

| The gates of Buochs, with its 5,300 souls, graciously open, welcoming travelers with its wooden houses, centuries-old relics bearing witness to the passage of time and the stories woven within. |

|

|

| The Via Jacobi then winds through the town’s narrow streets, respectfully admiring St Sebastian’s Chapel, also known as Nothelferkapelle, built in the late 17th century. At its heart, St Martin’s Church stands, a silent guardian of bygone centuries, its architecture a testament to past eras and human aspirations. |

|

|

| The road makes its way through a town stretching like a ribbon across the landscape, where each house seems to vie for charm and authenticity. Beneath their shingled roofs and graceful overhangs, these homes appear frozen in time, faithful custodians of the tales and legends that have shaped the lives of those who inhabit them. |

|

|

| Further on, yet another sacred stop, the Obgasskapelle Chapel, dedicated to Our Lady of Sorrows, stands, among many others, like a sentinel of the divine. Almost all the chapels that dot the route are jewels of regional Baroque, sporting prominent eaves and slender steeples, like fingers reaching skyward, bearing witness to the fervor and devotion of the faithful. |

|

|

Section 5: Above the lake in the meadows

Overview of the route’s challenges: The route presents no significant challenges, yet there are gentle undulations, occasionally with slightly steeper inclines.

|

The Via Jacobi, like a golden thread weaving through the tapestry of nature, slowly detaches from Buochs, sliding beneath the highway’s embrace.

|

|

|

| Here, you bid farewell to the azure mirror of Lake Luzern, a fleeting yet enchanting embrace. A narrow road emerges amidst the meadows, gently sloping up above the highway, that stretches towards the flat horizons of Stans. |

|

|

| The meadows, caressed by a gentle and benevolent slope, stretch along the farms like a velvet carpet woven by nature’s hand. Among these fertile fields, fruit trees stand proudly, their branches laden with promises. |

|

|

The countryside unfolds once more before your eyes, offering a symphony of colors and scents that rejuvenate the soul, evoking heavenly golf fairways.

| The road soon reaches a sort of small plateau. |

|

|

| Soon, the road slopes up, winding around Bürg/Ennerberg, like a silent pilgrimage through the heart of the countryside. There emerges a replica of the « Santa Casa di Loretto », a humble homage to the Virgin Mary, a precious stone among Europe’s sacred edifices. There are many Loretto chapels in Europe, designed in the Italian style and dedicated to the worship of Mary. |

|

|

The road, like a serpent, unfolds towards the hamlet of Bürg, within an hour’s walking distance from Stans.

| It climbs further, ascending to the crest of Waltersberg, amidst the labors of the farms, in a countryside that exalts the senses, where the intoxicating scent of the countryside blends with the sounds of animals and the emanations of the nurturing earth. |

|

|

| On the horizon, like a mirage, the silhouette of Stans emerges, playing hide-and-seek with the surrounding hills. |

|

|

| On the verdant slopes, cattle graze peacefully, punctuating the landscape with their familiar presence. Here and there, pigs, akin to free-spirited poets, venture in search of freedom. |

|

|

| Higher up, the road culminates at the summit of Waltersberg, where the modest chapel of Ste Anne sits, also known as Chäppelisitz, a humble guardian of ancient secrets, adorned with pious memories. |

|

|

| The route then lingers, caressing the expanse of Stans from its height, offering a breathtaking panoramic spectacle. In this oasis of serenity, even the hours seem to dance to the tranquil rhythm of nature, providing a refuge for travelers in search of peace and beauty. |

|

|

Section 6: Towards Stans, capital of the canton of Nidwalden

Overview of the route’s challenges: The route presents no significant challenges.

|

The Via Jacobi, like a wanderer descending from the hill on a wide grassy path, confidently enters the lush valleys of Hostetten, offering its travelers a bucolic spectacle painted in shades of green.

|

|

|

|

It then weaves among the rustic farms where pig farming thrives, infusing these fertile lands with a livelier spirit.

|

|

|

|

Soon, its harmonious course is interrupted by the crossing of the Engelberger Aa, not merely a watercourse, but a vital vein descending majestically from the peaks.

|

|

|

|

Beyond the river, a dirt path stretches flatly between farms, houses, and countryside towards St Heinrich. One will always be amazed by the order reigning in the woodpiles in front of the houses in the countryside.

|

|

|

|

Then, replacing this dirt path, a paved road takes over just as the Via Jacobi intersects with the railway and the road leading to Engelberg, nestled at the foot of the formidable Titlis, a jewel of winter sports in Central Switzerland. It’s strange that the Camino de Santiago ignores it, despite the presence of a Benedictine abbey and the legends of snow-covered slopes.

|

|

|

|

Beyond, the road gracefully winds to St Heinrich, where the humble chapel dedicated to Saint Henry stands, erected in the heart of the 19th century.

|

|

|

|

Continuing its journey, it soon enters the gates of Stans, skirting a towering wall that shelters the monumental and austere Fidelis College, pride of the canton of Nidwalden

|

|

|

|

Descending towards the center of the small town, it passes near the cemetery and the Beinhaus, a charnel house erected at the end of the 15th century, serving as both a place of worship and burial. Unfortunately, upon our passing, its doors remained closed.

|

|

|

|

It then arrives at the center of Stans (population 7,900), near the church. Many foreigners live here, in the capital of the canton of Nidwalden. Stans is the headquarters of Pilatus Aircraft, a global leader in single-engine turboprop aircraft. Approximately 2,000 employees work there.

|

|

|

|

The imposing church of St Peter and Paul, built on the remnants of an ancient Romanesque structure, bears witness to centuries past, its Gothic bell tower embracing the sky, while that from the 13th century, a testament to bygone times, proudly stands.

|

|

|

|

In the central square, amidst the frozen statues, stands the Winkelried Memorial, a sculptural work from 1865 by Ferdinand Schlöth, recalling the heroic sacrifice of this legendary figure, a cornerstone of Swiss history. Arnold von Winkelried belongs, like William Tell, to those legendary (or true?) heroes who shaped the early history of Switzerland. Winkelried is said to have allowed the Confederates to win victory over the troops of Duke Leopold III of Habsburg at the Battle of Sempach in 1386 (this one is historically attested). The Swiss couldn’t break through the lines of enemy foot soldiers. So, Winkelried, belonging to a wealthy family of Stans, allegedly threw himself onto the spears to breach the enemy lines after asking his comrades to look after his wife and children. The Swiss then infiltrated the enemy lines

|

|

|

|

At the dawn of the 18th century, an infernal blaze nearly consumed the village entirely, erasing the medieval splendor of yore. But from those ashes, a Baroque renewal emerged, once again illuminating the streets of Stans like a phoenix rising from its embers.

|

|

|

|

Among the architectural treasures, Rosenburg Castle stands as a timeless guardian, its medieval origins elevated by meticulous restorations, now offering a sumptuous setting for haute cuisine, under the aegis of the Höfli Foundation.

|

|

|

|

In these alleys, dwellings with discreet elegance nestle, adorned with shingles, like frozen works of art. The Winkelried House, now a museum, bears witness to the city’s rich cultural heritage, having hosted the great educator Pestalozzi.

|

|

|

|

Not far away, near the funicular leading to Stanserhorn, the Salzmagazin museum welcomes art enthusiasts, like a sanctuary dedicated to human creativity.

|

|

|

Accommodation on Via Jacobi

- Hotel Engel, Dorfstrasse 47, Emetten; 041 620 13 54; Hotel, dinner, breakfast

- Hotel Landgasthaus Schlüssel, Dorfstrasse 49, Emetten; 041 620 13 56; Hotel, dinner, breakfast

- B&B Bächli, Buochserstrasse 71, Beckenried; 041 620 64 68; Guestroom, breakfast

- Hôtel Rössli, Dorfplatz 1, Beckenried; 041 624 45 11; Hotel, dinner, breakfast

- Hôtel Seerausch, Buochserstasse, Beckenried; 041 501 01 31; Hoôtel****, dinner, breakfast

- Hôtel Boutique Schlüssel, Beckenried; 041 622 03 33; Hotel****, dinner, breakfast

- Hôtel Nidwaldnerhof, Dorfstrasse 12, Beckenried; 041 620 52 52; Hotel****, dinner, breakfast

- Camping Buochs, Seeeldstrasse, Buochs; 041 620 34 74; Camping, bungalows

- Famille Rölli-Lussi, Grossbächli, Buochs; 041 620 31 36/079 655 14 10; Guestroom (straw), breakfast

- Andreas Waser, Engelbergerstrasse, Buochs; 041 610 50 27/079 487 25 66; Guestroom (straw), breakfast

- Hôtel Krone, Dorfplatz 2, Buochs; 041 624 67 77; Hotel***, dinner, breakfast

- Monika&Peter Waser, Buochserstrasse 50, Stans; 041 610 81 25/078 809 47 99; Guestroom (straw), breakfast

- B&B Odermatt, Wanghof, Stans; 041 610 01 46/079 215 40 93; Guestroom (straw), breakfast

- B&B Zemp-Koller, Knirigasse 5, Stans; 041 610 66 43/079 771 27 00; Guestroom, breakfast

- Stanserhof, Stansstaderstrasse 20, Stans; 041 619 71 71; Hotel***, dinner, breakfast

- Hôtel Engel, Dorfplatz 1, Stans; 041 619 10 10; Hotel***, dinner, breakfast

Finding accommodation on this stage shouldn’t pose major difficulties. You’ll be in cities with all the necessary amenities. However, it’s still wise to make reservations for peace of mind.

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 7: From Stans to Sachseln |

|

|

Back to menu |